September 11 meant something else for thousands of Americans in 1942.

September 11, 1942: The first Japanese American inmates arrived at the Topaz War Relocation Center in Central Utah.

It was called the Central Utah Relocation Center. Or Abraham Relocation Center. But the name was too long — and so it became Topaz, named after the mountain nine miles away.

But nothing about Topaz was polished.

Utah’s governor, Herbert B. Maw, actively opposed the relocation of Japanese Americans into his state. “If they are dangerous in California, they will be dangerous in Utah,” he stated. But eventually, Maw gave in.

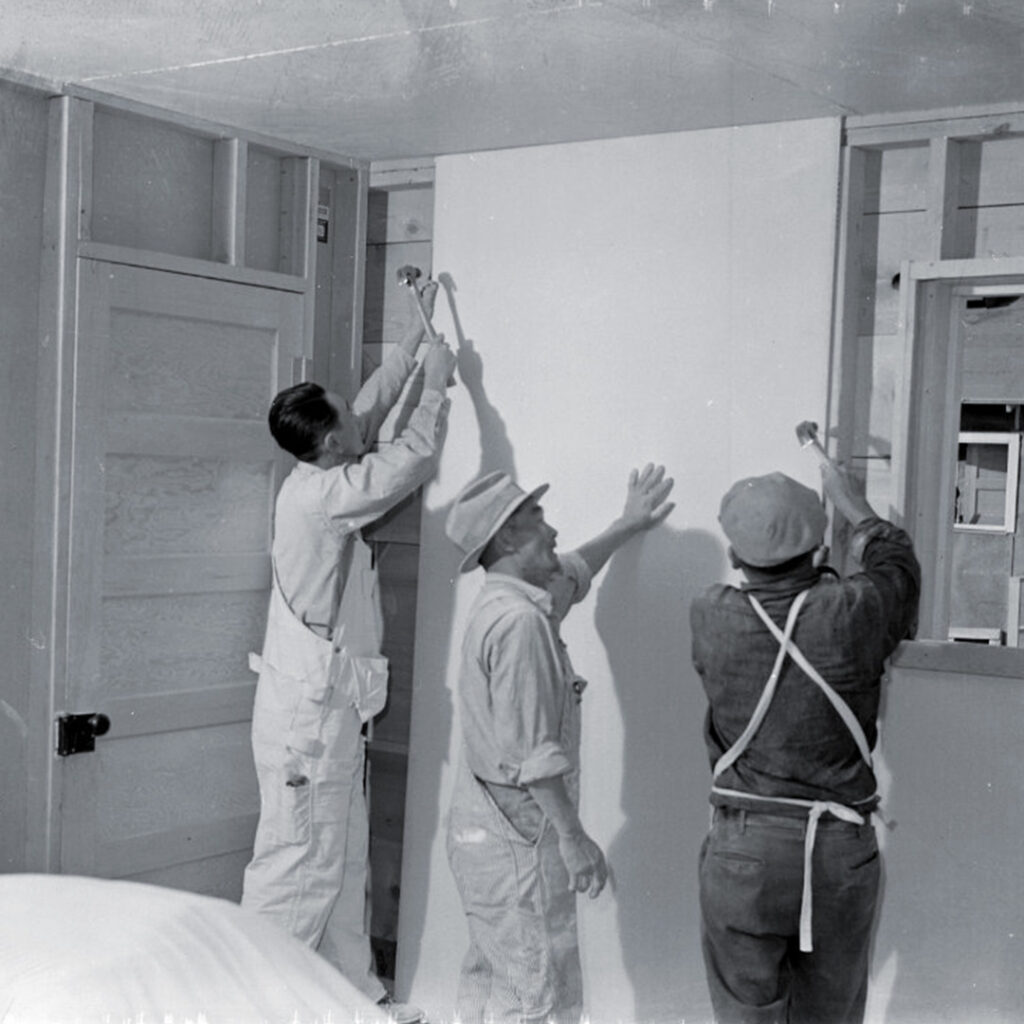

When the first inmates arrived from the Tanforan racetrack in California on September 11, 1942, the camp wasn’t even finished. There was no furniture. No proper sanitation. And in some cases, no assigned rooms at all. Incarcerees had to scavenge leftover construction wood to build their own tables, beds, and shelves.

More than 9,000 Japanese Americans, mostly from San Francisco, would be incarcerated here during WWII, behind barbed wire in a barren, inhospitable corner of Utah.

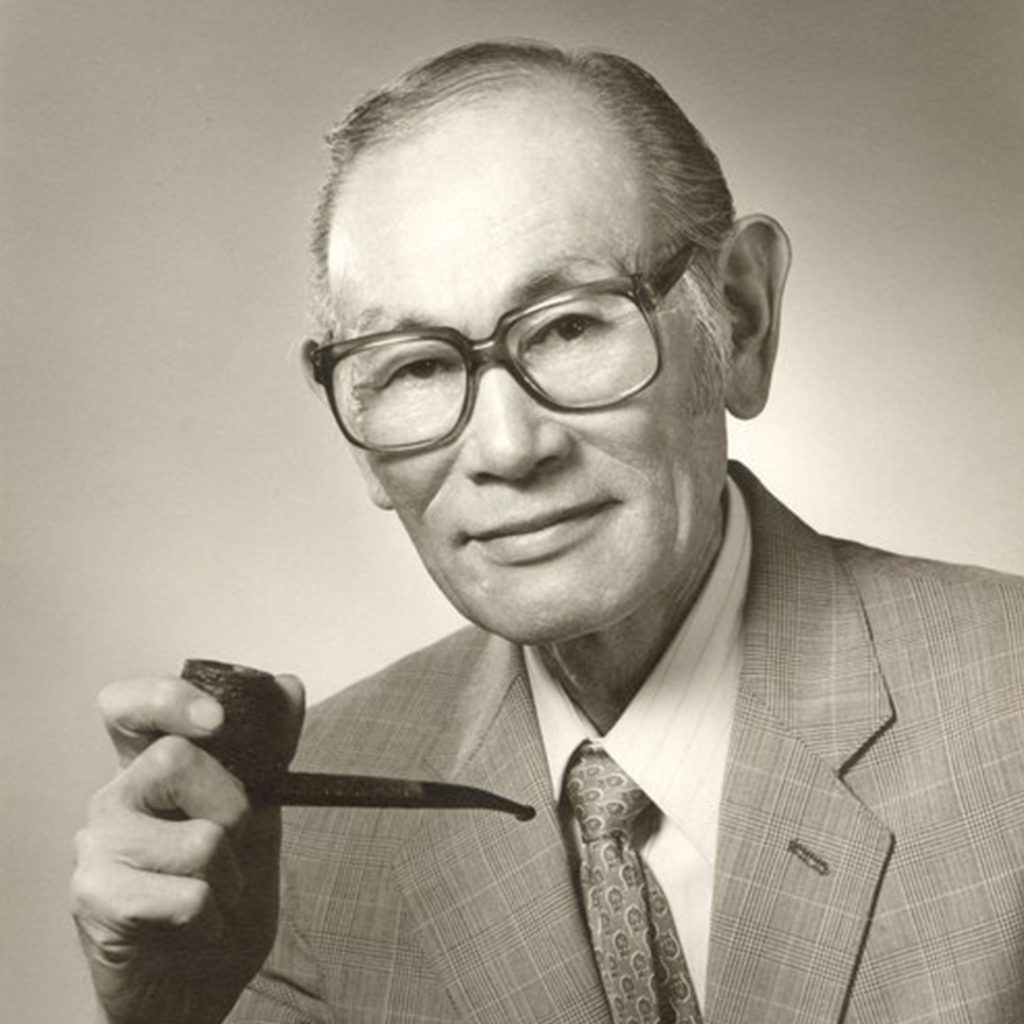

Despite the grim conditions, Topaz became home to an astonishing number of artists and civil rights activists. Fred Korematsu and Mitsuye Endo were two of the most important names in the legal fight against incarceration. Richard Aoki was an early member of the Black Panther Party. Yuji Ichioka was known to have coined the term Asian American and became a leading figure in its movement.

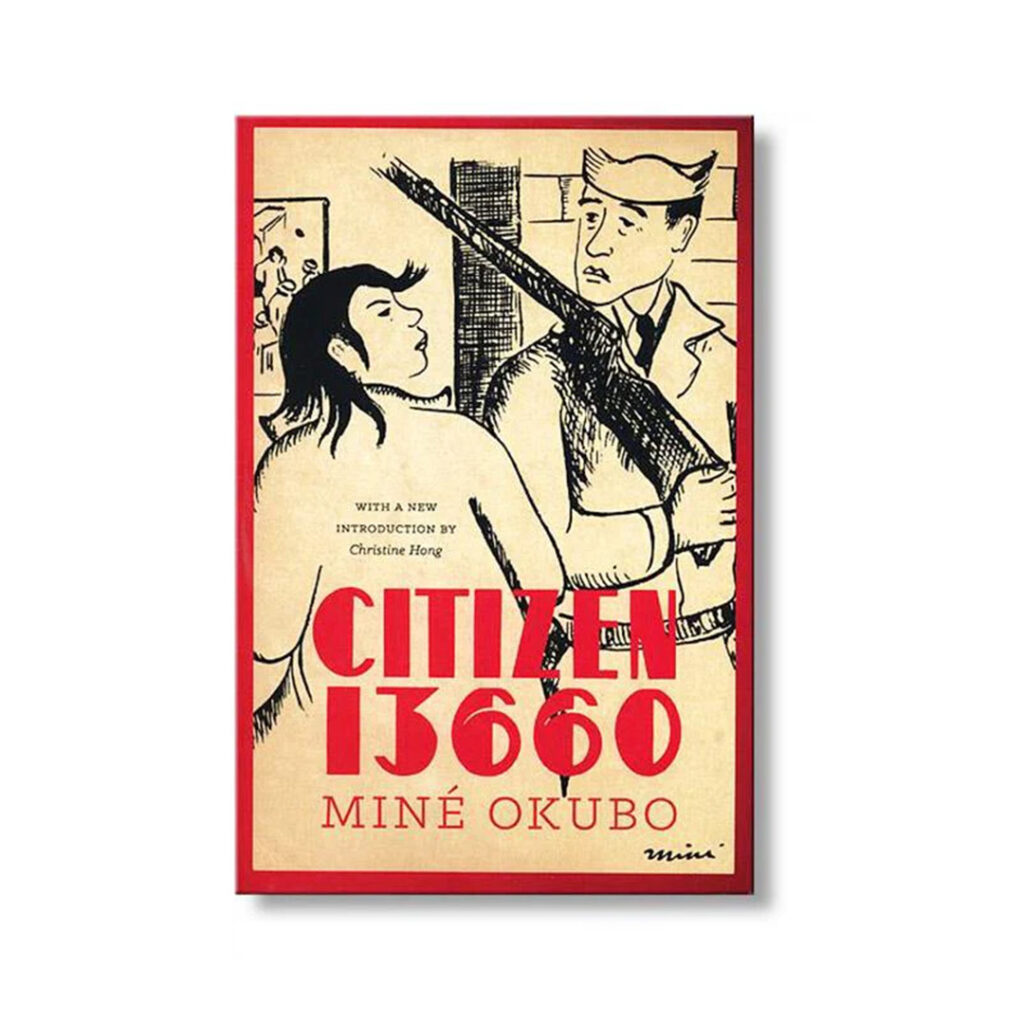

Artists Chiura Obata, Miné Okubo, and George Hibi, used art as a form of resistance and documentation. Illustrator/animator Willie Ito is still using his skills as a way to tell the story of incarceration through a children’s book story, “Hello Maggie!”

Jack Soo (born Goro Suzuki) — who would go on to fame as an actor and singer.

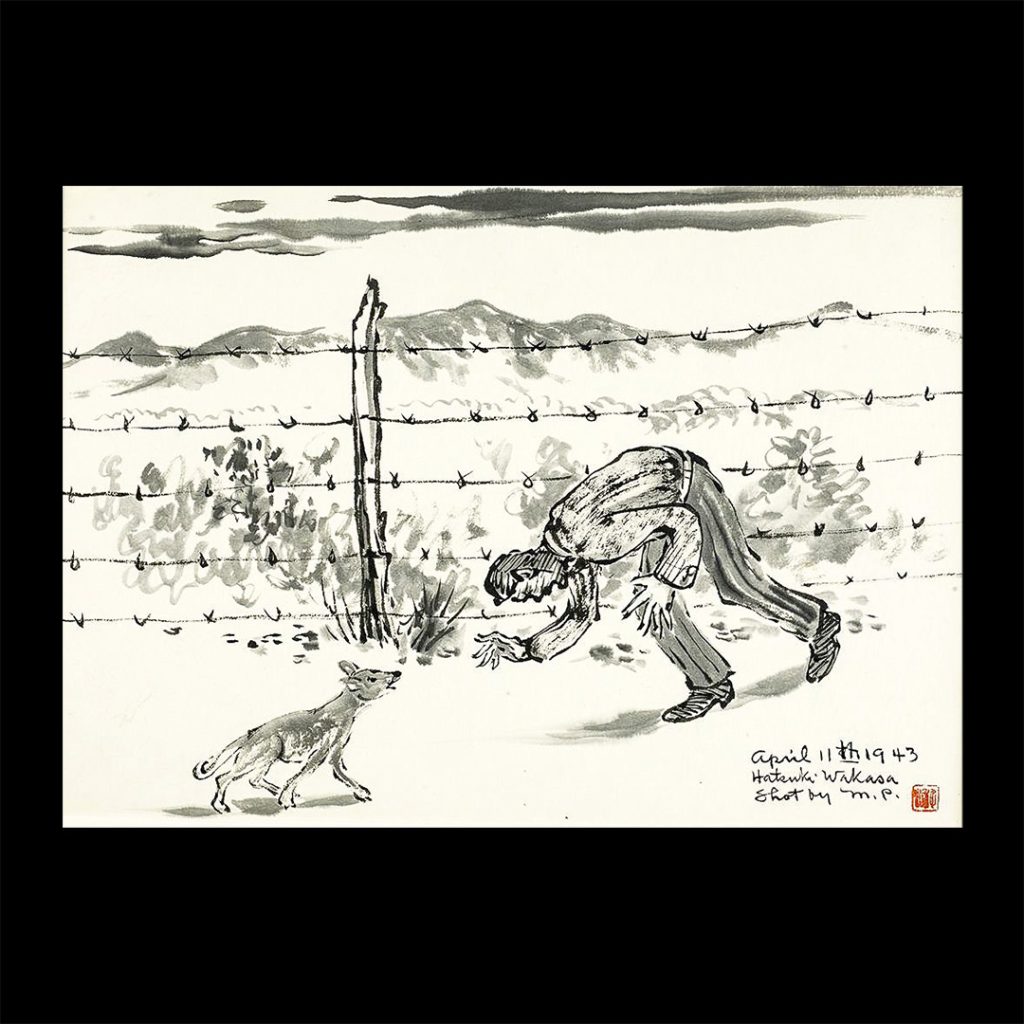

Topaz was also the site of one of the most tragic — and quietly buried — events in Japanese American incarceration: the murder of James Hatsuaki Wakasa, a man who was shot and killed by a guard near the fence while walking his dog. Too little too late, but after his death, the military decided that officers who had been at war in the Pacific would not be assigned to guard duty at Topaz.

The camp was finally shut down on October 31, 1945. But not much was left behind. The land was sold. The buildings were auctioned off. Even the water pipes were ripped out and resold. In 1976, the Japanese American Citizens League placed a single stone marker on the corner of the central site — the only visible sign that 8,000 people once lived behind fences there.

But in 2015, the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah, formally opened. By 2017, the Topaz Museum and Board had purchased 634 of the 640 acres of the original internment site.

Today, September 11 obviously means something else. But that doesn’t mean this one should be forgotten, either.

Further Reading:

The Murder of James Wakasa at Topaz by High Country News

Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo

Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah