It became home of the disloyal enemies.

July 31, 1943: Tule Lake was redesignated as a segregation center for “disloyal” Japanese Americans.

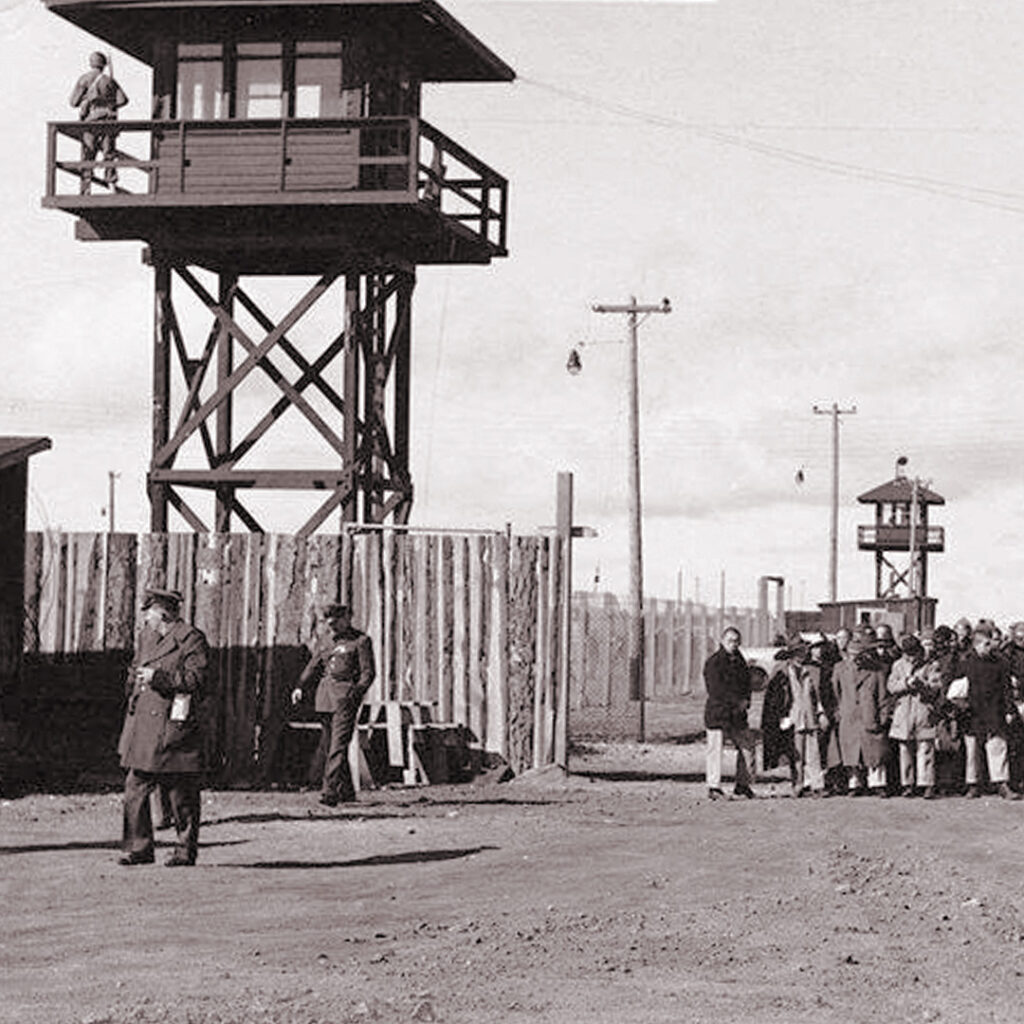

What began as one of ten War Relocation Authority (WRA) incarceration camps became something far more severe — the highest-security prison camp in the entire system.

A loyalty test for enemy aliens

Earlier that year, the U.S. government issued a so-called loyalty questionnaire to all adults imprisoned in the camps — including elderly Issei who weren’t even allowed to become U.S. citizens. The questionnaire was confusing, coercive, and laced with double meanings. Two questions in particular — Questions 27 and 28 — created mass confusion and fear:

- Q27 asked if men would be willing to serve in the U.S. Army.

- Q28 asked everyone to “forswear allegiance” to the Japanese emperor — even if they never had allegiance in the first place.

Answering “no” — even out of protest or for practical reasons — branded someone “disloyal.” The government then began separating these “no-no” respondents from the rest. Roughly 6,500 so-called “loyals” were transferred out of Tule Lake to six of the other camps.

The dumping ground of the troublemakers

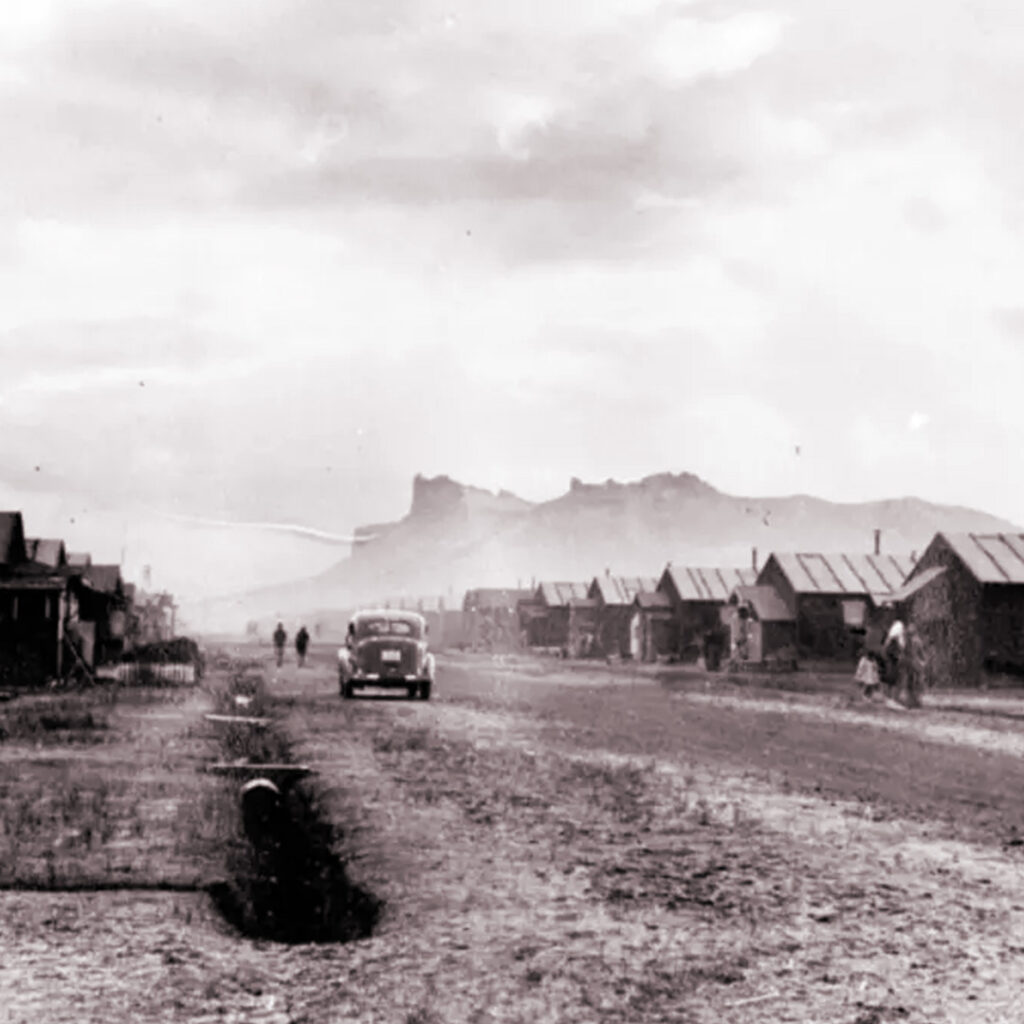

After its redesignation on July 31, Tule Lake ballooned to over 18,000 incarcerees — most of them transferred from other camps across the country. It became overcrowded, over-policed, and deeply unstable.

The government fortified Tule Lake like a military base:

- Barbed wire fences were raised taller

- Guard towers increased from 6 to 28

- 1,000 military police with tanks and armored cars were stationed

- A stockade — a prison within a prison — was constructed inside the camp

Anyone who resisted — even peacefully — risked being thrown into solitary confinement without due process. Further fueling the unrest was the fact that nearly one-third of Tule Lake’s population consisted of “loyals” who just didn’t want to leave when segregation was enforced. The resulting tensions were explosive.

Best wasn’t the best

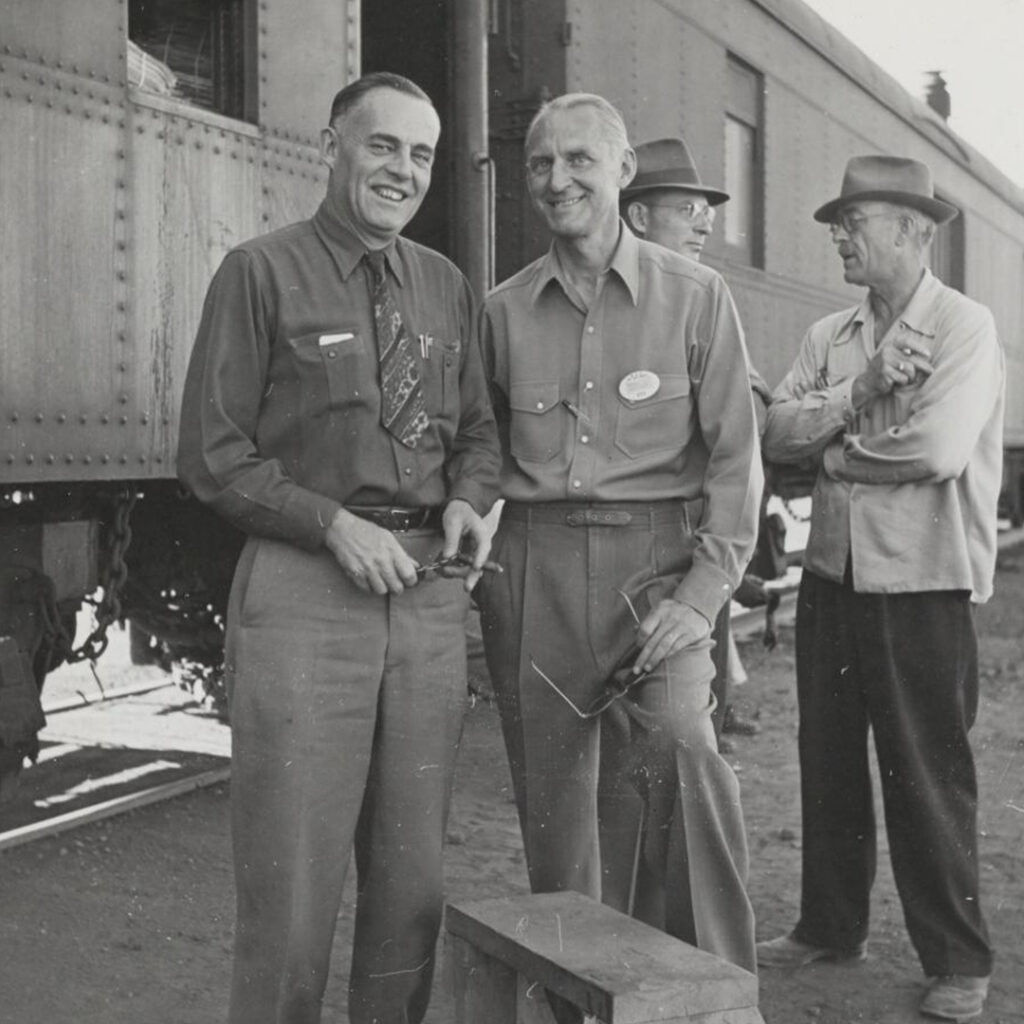

Despite the conditions, Tule Lake became a center of resistance. Incarcerees organized protests, strikes, and petitions. They were fed up — not just with imprisonment, but with having their loyalty and humanity constantly questioned. Raymond Best, appointed Project Director on August 1, 1943, did little to de-escalate.

When tensions rose, he called in the army. When laborers went on strike, he brought in outside strikebreakers from other camps, who, in two days, earned what Tule Lake workers made in a month. Chaos, confusion, and resentment only deepened.

A number of incarcerees even renounced their U.S. citizenship in protest — decisions that many later sought to reverse after understanding the emotional and legal consequences. It took some of them 14 years of legal battles to restore their American citizenship.

A legacy of the maximum internment camp

Tule Lake was the last of the ten WRA camps to close, in March 1946. It remains one of the most emotionally charged and misunderstood chapters of the Japanese American incarceration story.

But it was also a place where voices rose, solidarity formed, and the truth refused to stay silent — even behind barbed wire.

It was the largest of all the camps, not just in population, but in scale and infrastructure. Despite all its tensions and issues, Tule Lake boasted: a furniture factory, a tofu factory, a hog farm and slaughterhouse, a bakery that produced goods for the camp, a beauty shop, fish store, funeral parlor, and shoe repair shop, multiple cooperative stores, eight Buddhist temples and three Christian churches, four judo halls, and vast agricultural fields that helped feed not only Tule Lake, but other camps as well.

It was perhaps the most intense Japanese American incarceration camp during the war. The home of the most misunderstood. The prisonest of the prisons.