The only Asian American leader in the Black Panther Party was an FBI informant.

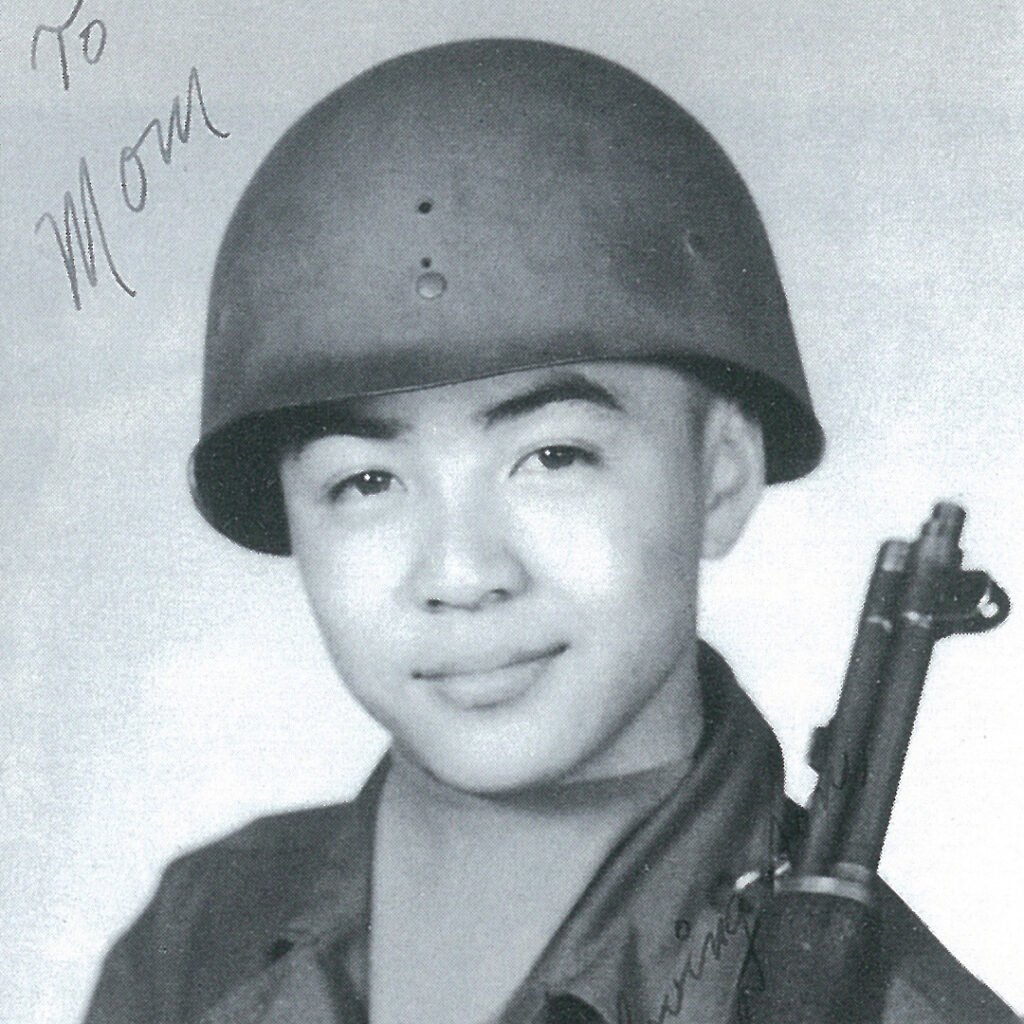

November 20, 1938: Richard Aoki, a Japanese American activist, revolutionary, Topaz incarceree, U.S. Army veteran, and the only Asian American leader in the Black Panther Party, was born in San Leandro, CA. His legacy remains one of the most complex in civil rights history.

Richard Masato Aoki spent his early childhood behind barbed wire at the Topaz concentration camp. He later admitted that the incarceration shattered his family. His father joined a gang and eventually abandoned them.

After the war, the remaining family returned to California and rebuilt their lives in West Oakland. They did so without a father and in one of the most diverse and politically charged neighborhoods.

West Oakland shaped him. He grew up among Black classmates, musicians, future organizers, and communities living with daily segregation and police surveillance. These early experiences deeply influenced the alliances he later formed.

As a teenager, Aoki was arrested for petty crimes. A judge offered him a deal: enlist in the U.S. Army and the offenses would be removed from his record. His military service gave him weapons training, discipline, and tactical experience, which later became controversial once he joined the Panthers.

The Making of a Revolutionary

Aoki enrolled at Merritt College in the 1960s, where he met Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. They bonded over shared frustrations, ambitions, and understanding of American contradictions.

Newton and Seale asked Aoki to join their new organization, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. He became one of its earliest field marshals. He provided structure, political education, and, according to many accounts including his own, weapons.

He was viewed as fully committed to the Panthers’ mission. He marched. He organized. He spoke. He put himself at risk.

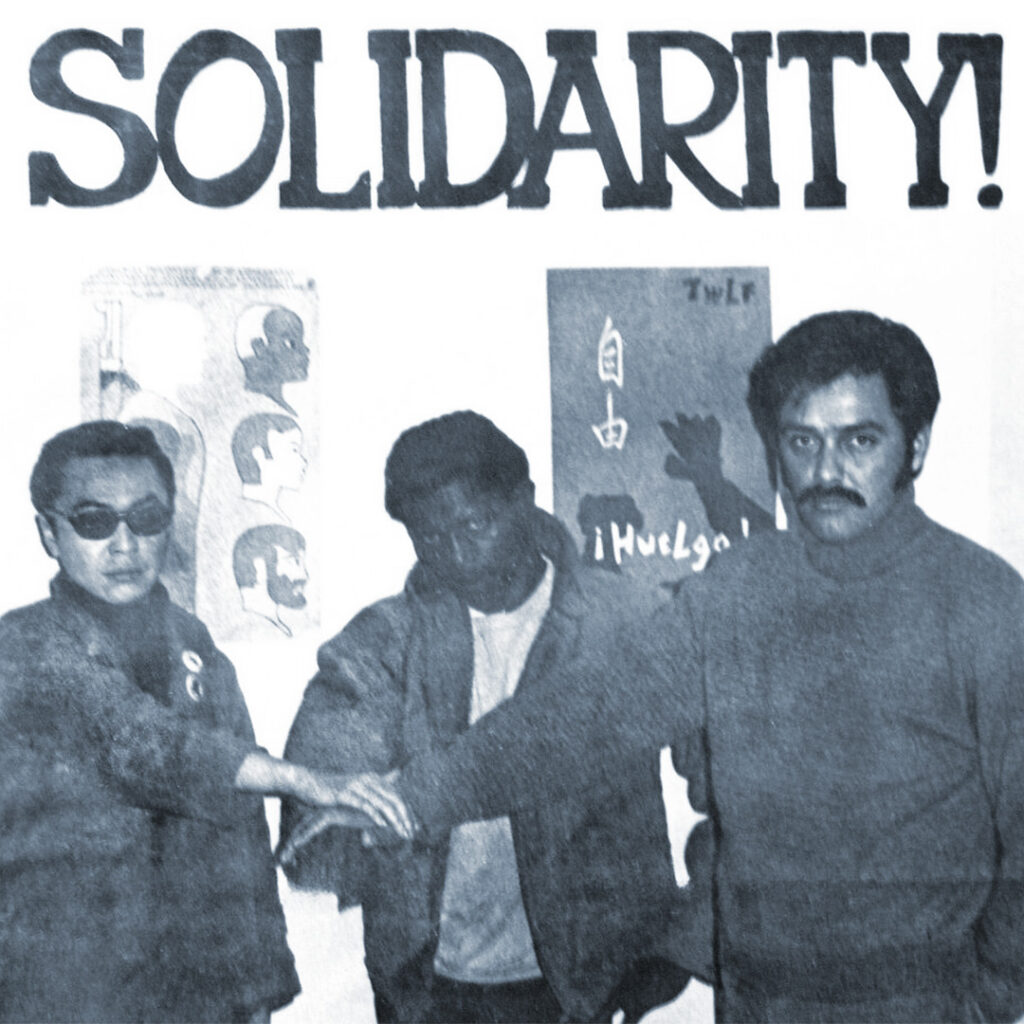

Aoki also became a key member of the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA), which connected Asian American, Black, and Latino struggles for civil rights. Through both groups, he became a bridge between movements often treated separately in the historical record.

The FBI Files

In 1971, Aoki returned to Merritt College as an instructor in social service work. For the next twenty-five years, he was respected as a counselor, teacher, and administrator.

Then in 2012, everything changed. Investigative journalist Seth Rosenfeld uncovered documents identifying Aoki as an FBI informant. Additional releases showed that Aoki began informing years before joining the Panthers, while still in the army.

Friends and activists were stunned. Many refused to believe it. Others accepted the documents as undeniable evidence. Aoki himself during one interview, when the reporter asked if it was wrong to assume he was an informant, he vaguely replied, “I think you are,” but added, “People change. It is complex. Layer upon layer.”

What is certain is that the government aggressively monitored both Black and Asian American activists during this period. Aoki lived in that pressure cooker. And he carried secrets to the end of his life.

A Legacy That Is Not Black and White

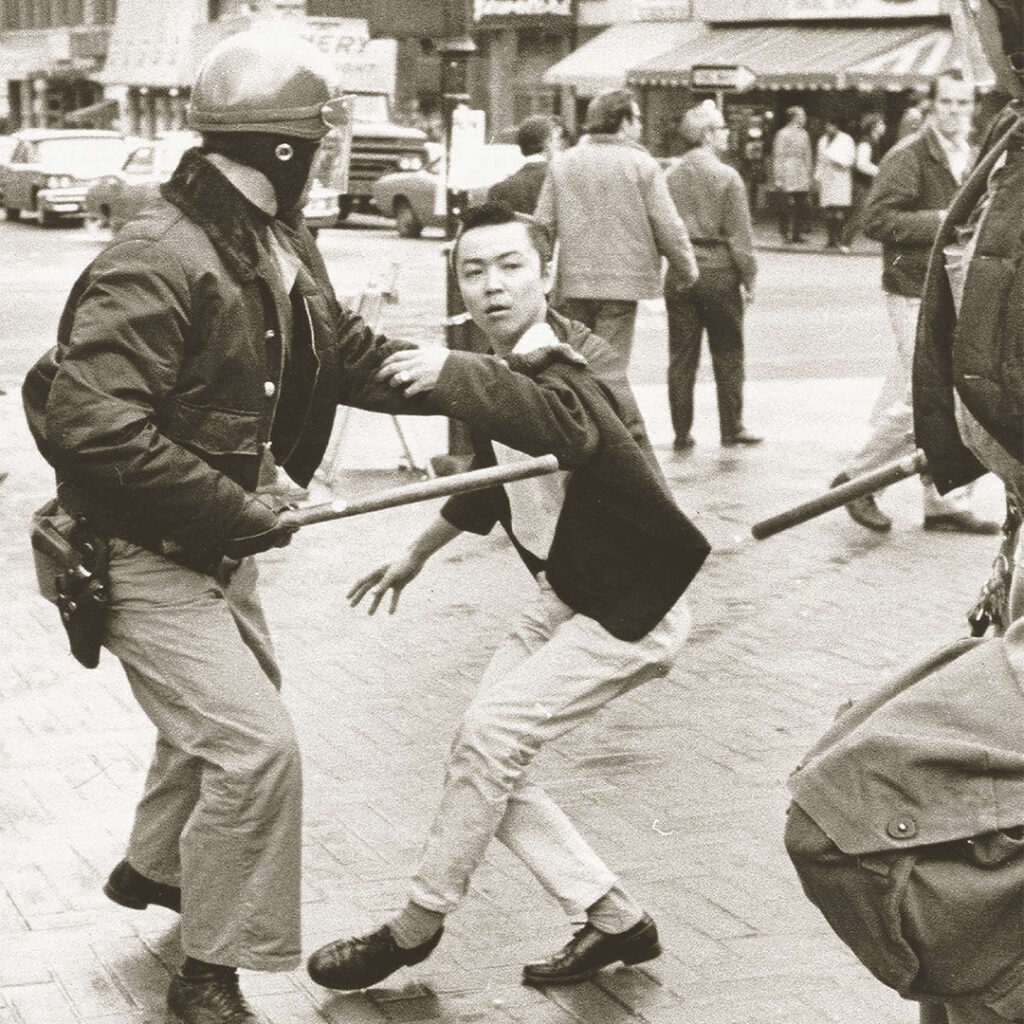

Richard Aoki’s story resists easy framing. His activism was significant and visible. In 1969 when a strike erupted, an estimated 147 protesters were arrested, including Aoki. Decades later, when UC Berkeley faced new threats to its ethnic studies program, he returned to stand with students once again. Whatever his ties to the FBI had been, they were long behind him by that time.

At his memorial service at Wheeler Hall in 2009, Bobby Seale and other activists remembered him as a fearless leader and a servant of the people. Aoki once said, “My joining the Black Panther Party was about being in the right place at the right time, or the wrong place at the wrong time, depending on how you look at it.” It was a cryptic statement, and perhaps the most honest one he gave.

Richard Aoki’s story does not fit neatly into categories of hero or traitor. It asks us to sit with an uncomfortable ambiguity.