In 1942, U.S. Army was quietly conducting death marches in America.

July 27, 1942: Two disabled Japanese men were shot during their march to the prison camp.

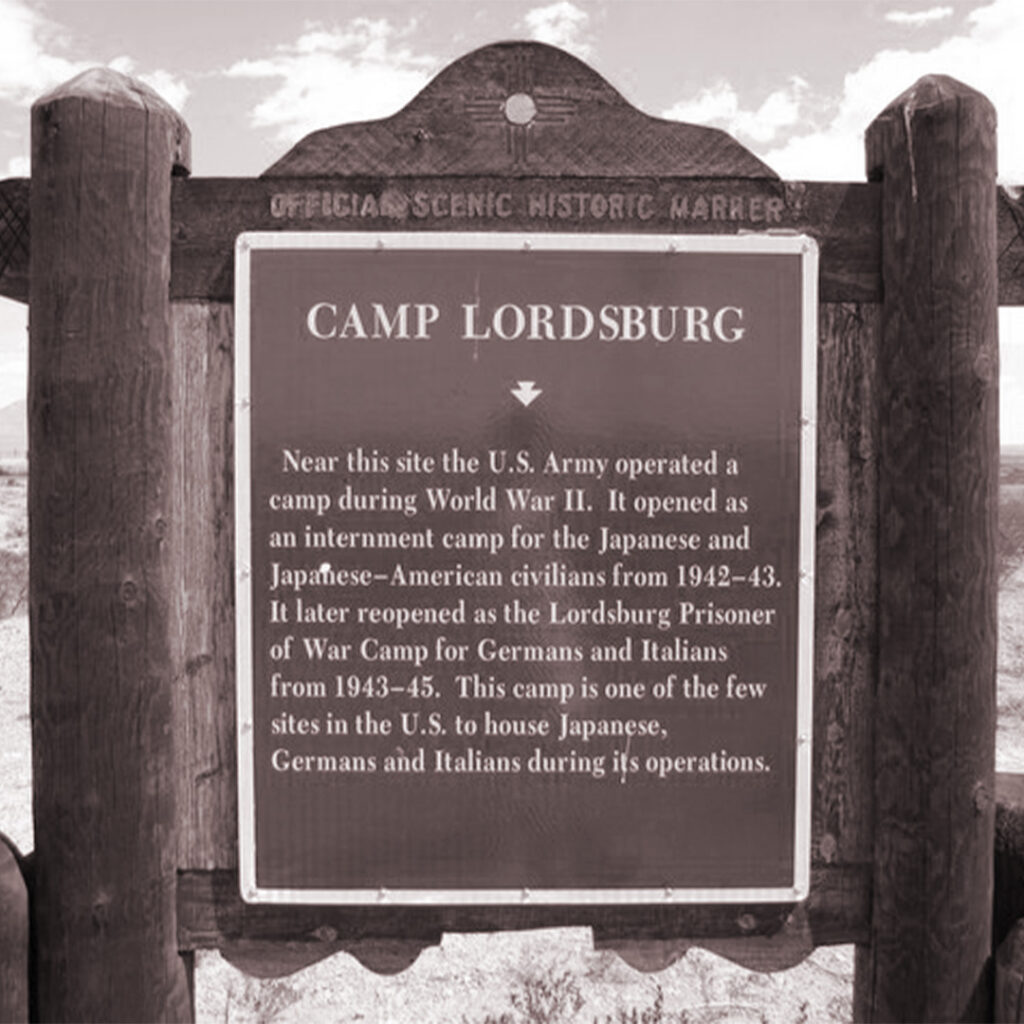

Deep in the New Mexico desert, hundreds of Japanese immigrants had been rounded up from Hawaiʻi and California and imprisoned in an army incarceration camp called Camp Lordsburg. Many of them were elderly or disabled Issei (first generation Japanese migrants) — not threats to national security, but victims of suspicion and wartime hysteria. They were civilians. They hadn’t been charged with any crimes. And yet they were treated like POWs — or worse.

To avoid alarming the local population, the army would unload the internees from the train at an isolated station two miles away from camp, in the dark, and force them to march through the desert in silence. These nighttime death marches weren’t just a one-time event — they were standard practice. And on July 27, 1942, it turned deadly. Although, this wasn’t the first time this happened.

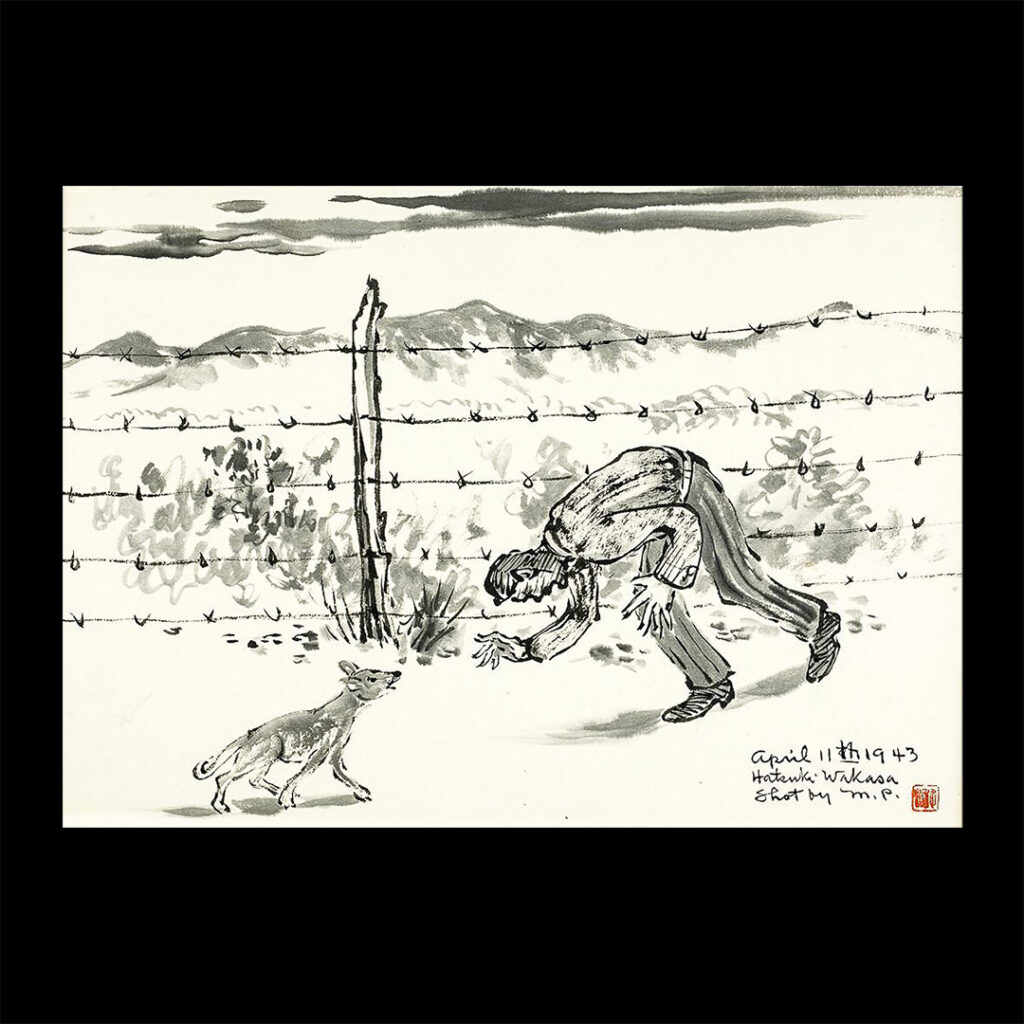

That night, two men — Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura — fell behind. Both were elderly and had been hospitalized multiple times. Kobata had effects from tuberculosis. Isomura had spinal damage from a boating accident. A guard claimed the men were trying to escape and opened fire, killing both.

The story didn’t hold.

Eyewitnesses said the men had no intention of fleeing. They were simply too frail to keep up. According to the Geneva Convention of 1929, even enemy POWs could only be shot while attempting to escape under certain conditions, and this was not one of them. These men were not armed. They were not soldiers. They posed no threat.

And yet, the killings were covered up as justified.

That same year, it was revealed that Colonel Clyde Lundy, the camp’s commander, had also violated the Geneva Convention by using Japanese internees as forced labor to build military infrastructure — including a landing strip. When some of the men refused, he retaliated by reducing rations and threatening punishments.

Eventually, internees pushed back. Their complaints reached Eighth Army headquarters at Fort Bliss, and an investigation followed. The result?

- Colonel Lundy was forced into retirement.

- The Camp Lordsburg facility was shut down.

- The incarcerees were transferred to Camp Santa Fe.

It was a rare case where protest worked — but only after lives were lost.

Today, Camp Lordsburg is largely forgotten. But there are barracks, concrete, and foundations of some of the buildings at the camp can still be visited, in addition to a historical marker that is located near the site. The marker reads as follows: Camp Lordsburg – Near this site the U.S. Army operated a camp during World War II. It opened as an internment camp for Japanese and Japanese-American civilians from 1942-43. It later reopened as the Lordsburg Prisoner of War Camp for Germans and Italians from 1943-45. This camp is one of the few sites in the U.S. to house Japanese, Germans and Italians during its operations.

It happened here.

We need to remember. Because it could be happening again.