California’s First Japanese Millionaire Failed English.

February 13, 1864: George Shima (born Kinji Ushijima), who would become California’s first Japanese millionaire and earn the nickname “The Potato King,” was born in Fukuoka, Japan.

Before he became one of the most powerful agricultural figures in California, Ushijima failed an entrance examination atTokyo University of Commerce (now Hitotsubashi University).

The subject that gave him the most trouble? English. For many, that failure would have been the end of the story. For him, it became the beginning. In 1889, at 25 years old, he emigrated to San Francisco determined to conquer the subject that had defeated him.

He took on odd jobs. Washed dishes. Worked in restaurants. Saved money. Studied English.

And like many Japanese immigrants of the era, he entered agriculture — one of the few industries open to him.

Tokyo University of Commerce (now Hitotsubashi University), where Kinji Ushijima attempted the entrance examination he would not pass, because he failed English.

Courtesy of Open SF History

San Francisco, 1889. A 25-year-old immigrant named Kinji Ushijima arrived here determined to master the English language that had once defeated him.

Courtesy of San Joaquin County Historical Museum

George Shima supervising laborers, c. 1913. He moved from farmhand to labor contractor and manager early on, which laid the foundation for his agricultural empire.

Courtesy of San Joaquin County Historical Museum

Caricature of George Shima, c. 1910. His influence in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta was so large, he was celebrated by some, resented by others.

The Rise of the “Potato King”

Under the American name George Shima, he first turned to labor contracting, supplying Japanese farm workers to white farmers.

Successful enough to accumulate capital, he began leasing inexpensive farmland in California’s Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, land considered undesirable by white American farmers.

After draining and diking the marshland, he discovered something others had missed. The soil was perfect for potatoes.

At one point, he controlled or influenced roughly 85% of California’s potato production — a staggering share of the market. Newspapers began calling him the “Potato King.”

Strategy Against Racism

He wasn’t just a farmer. He was a strategist. He navigated land leasing restrictions, racial hostility, and growing anti-Japanese agitation. Shima adapted through partnerships and corporate structures.

Shima donated generously to universities, supported Japanese students, and invested in community institutions. He built wealth in a system designed to keep him out.

Yet even as a millionaire, he continued to face discrimination.

Japanese farmers were accused of undercutting white growers. Anti-Asian rhetoric grew louder in California politics. The same country that offered opportunity also erected barriers.

Courtesy of UC Berkeley Bancroft Library

Shima standing alongside Admiral Robert Coontz and California leaders. A Japanese immigrant who once struggled with English moved in the political circles.

Courtesy of San Joaquin County Historical Museum

George Shima (far right) at a banquet on Bacon Island in California’s Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta, 1915. The “Potato King” was an influential agricultural figure.

Courtesy of California State University Domingues Hills

“An Appeal to Justice,” published by George Shima in response to California’s proposed anti-Japanese land measures, pleading simply to be treated as an American.

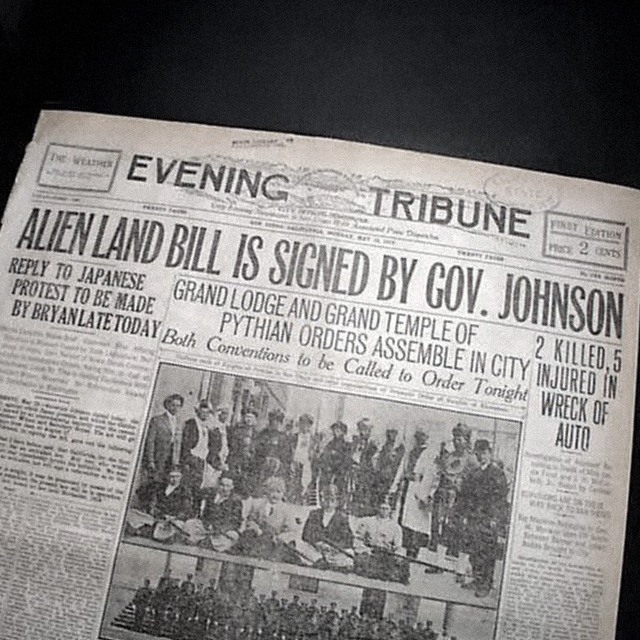

Headline announcing California’s Alien Land Law of 1913 — the first statewide law designed to keep Japanese immigrants, especially someone like Shima, from owning farmland.

Alien Land Laws

Shima had already begun purchasing land rather than simply leasing it. His visibility as a successful Japanese farmer — and especially as a millionaire — became ammunition for those who argued that Japanese growers were “taking over” California agriculture.

He became the first president of the Japanese Association of America and fought unsuccessfully against the California Alien Land Law of 1913, legislation written specifically to block Asian land ownership.

The California Alien Land Law prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural land, a phrase crafted to target Japanese immigrants, who were barred from naturalization under federal law.

The End of A Dream

The state now barred them from owning the land they farmed, while severely restricting the land they could lease. By the 1920s, Shima was forced to dismantle much of his empire — a fate that would also confront fellow agricultural magnate Kanaye Nagasawa, California’s famed “Wine King.”

Tired of persistent prejudice, Shima eventually decided to return to Japan. He died suddenly on March 27, 1926, while traveling home.

Shima crossed an ocean to master English. He mastered agriculture instead. In doing so, he reshaped California farming, even as the state tried to push him out.

Courtesy of San Joaquin County Historical Museum

George Shima (right), photographed in the early 1920s with unknown men. By 1913, his "Shima Fancy" brand valued at more than $18 million ($282,528,239 today).

Courtesy of Kurume City Board of Education

The man once dismissed for failing English became California’s “Potato King.” Like many first-generation Japanese American fortunes, his empire did not outlive him.