Passionate to teach art, he turned an incarceration camp into an art school.

November 18, 1885: Chiura Obata, Japanese American artist, art professor, and founding director of art schools within the incarceration camps, was born in Japan.

Chiura Obata grew up in a large family from Okayama, Japan. At five he already showed a flair for drawing. By seven, he began formal training, in both Western painting and modern Japanese art, but his deepest foundation came from sumi ink and brush.

In 1903, at seventeen, Obata came to the United States. His plan was temporary. America was supposed to be a stop on the way to Paris, where he hoped to study European art. But his time in California changed him. After working as an illustrator and commercial decorator, he found success as a painter, eventually becoming known for landscapes that blended Japanese technique with the Western eye for space and light.

By the 1930s he was hired as an art professor at UC Berkeley. His career was flourishing. His students admired him. Berkeley embraced him. Then the war began.

A Community Turns Hostile

Obata and his wife Haruko ran an art supply store in Berkeley. Days after the Pearl Harbor attack, someone fired shots into the store windows. They closed the shop. Every class they offered had to be canceled. Their world, carefully built over decades, began to collapse.

When Executive Order 9066 forced Japanese Americans to prepare for eviction, Obata made a painful decision. He sold many of his paintings and prints. The money went not to himself, but to a scholarship for a student “regardless of race or creed, who has suffered the most from this war.”

Not everybody turned hostile. University President Robert Gordon Sproul, a close friend, offered to store many of Obata’s remaining works for safekeeping. It was one of the few acts of support he received during that period.

Creating Art Under Confinement

In April 1942, Obata was sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center. Behind the horse stalls that served as living quarters, he found a way to keep teaching.

By May, he and several fellow artists created an art school with more than 900 students. They funded it themselves, with donations from friends at UC Berkeley, including photographer Dorothea Lange.

The school became a haven. It offered 95 classes each week in 25 subjects. Camp administrators supported the effort because it kept people occupied. Obata and his colleagues were even allowed to order materials from Sears Roebuck or purchase supplies in town.

The work flourished. In July, artworks created inside the camp were exhibited to the outside world.

Topaz: A New School in the Desert

In September 1942, Obata was transferred to the Topaz War Relocation Center in Utah, where he founded and directed the Topaz Art School. Sixteen instructors taught twenty-three subjects to more than six hundred students. Even in a hostile desert, Obata created a world where beauty could still be practiced, shared, and taught.

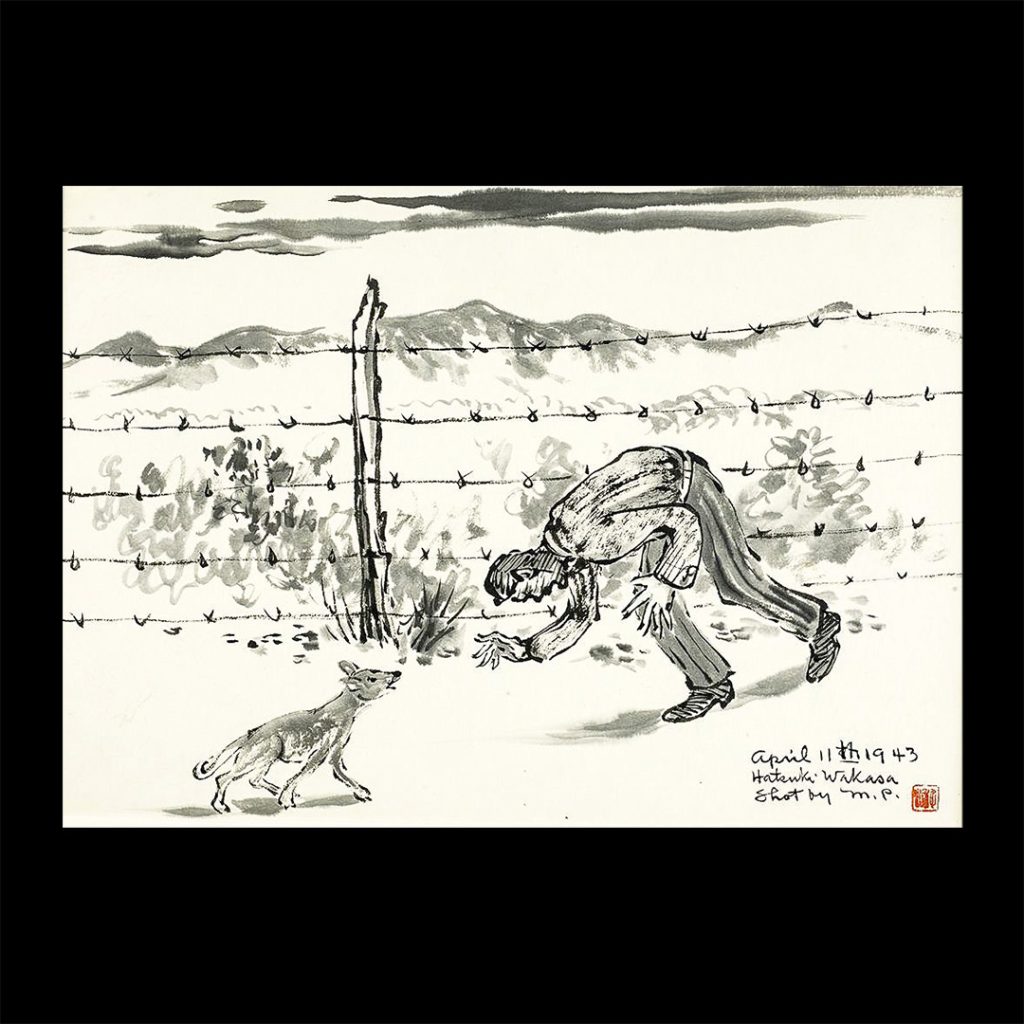

But by 1943, tensions inside Topaz had escalated. The loyalty questionnaire and the killing of James Hatsuaki Wakasa left the camp on edge. Obata had been classified “loyal,” which allowed him to leave camp to teach at nearby universities and churches. For some inmates, already angry and disillusioned, this privilege made him a target of suspicion.

One night, after leaving the showers, he was attacked by a fellow inmate who believed he was a spy. Obata spent two weeks in the camp hospital. For his own safety, he was released from Topaz immediately afterward.

Post War

When the exclusion ban was lifted in 1945, Obata returned to UC Berkeley and was reinstated as an instructor. He regained his life piece by piece. In 1949 he became an associate professor. In 1950 he and Haruko purchased a home in Berkeley’s Elmwood district, the same neighborhood they had lived in before the war.

He retired as Professor Emeritus in 1953, and in 1954 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen after immigration laws finally allowed Japanese immigrants to apply.

Chiura Obata believed in the power of art.

At Tanforan and Topaz, his schools became symbols of perseverance. His students painted mountains, storms, memories, and hope. They painted a world beyond the fences. In the middle of a shameful chapter of American history, Obata showed that creativity could be an act of resistance — a way to channel their energy into something positive, meaningful, and lasting.