He went from a “Jap” behind barbed wire to a respected American soldier in postwar Japan.

December 1, 1921: Claude Akira Mimaki was born in San Gabriel, California, the Nisei son of two immigrants from Kumamoto, Japan.

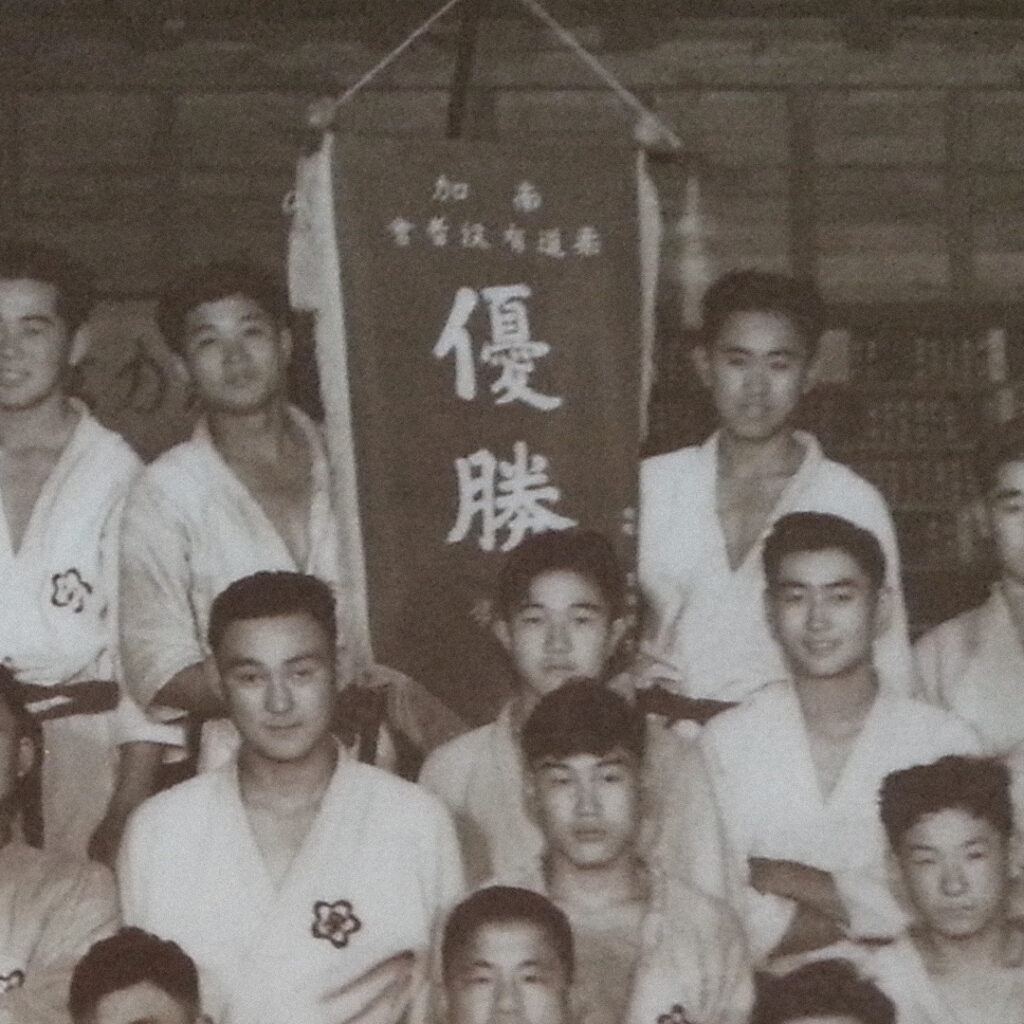

Claude spoke mostly Japanese at home early on. When he got into fights at school, he yelled in Japanese too. Slowly he made friends and grew up like any American kid in the San Gabriel Valley in the 1920s — school, friends, sports — except he and his cousin George were almost always the only Asian faces in their classrooms.

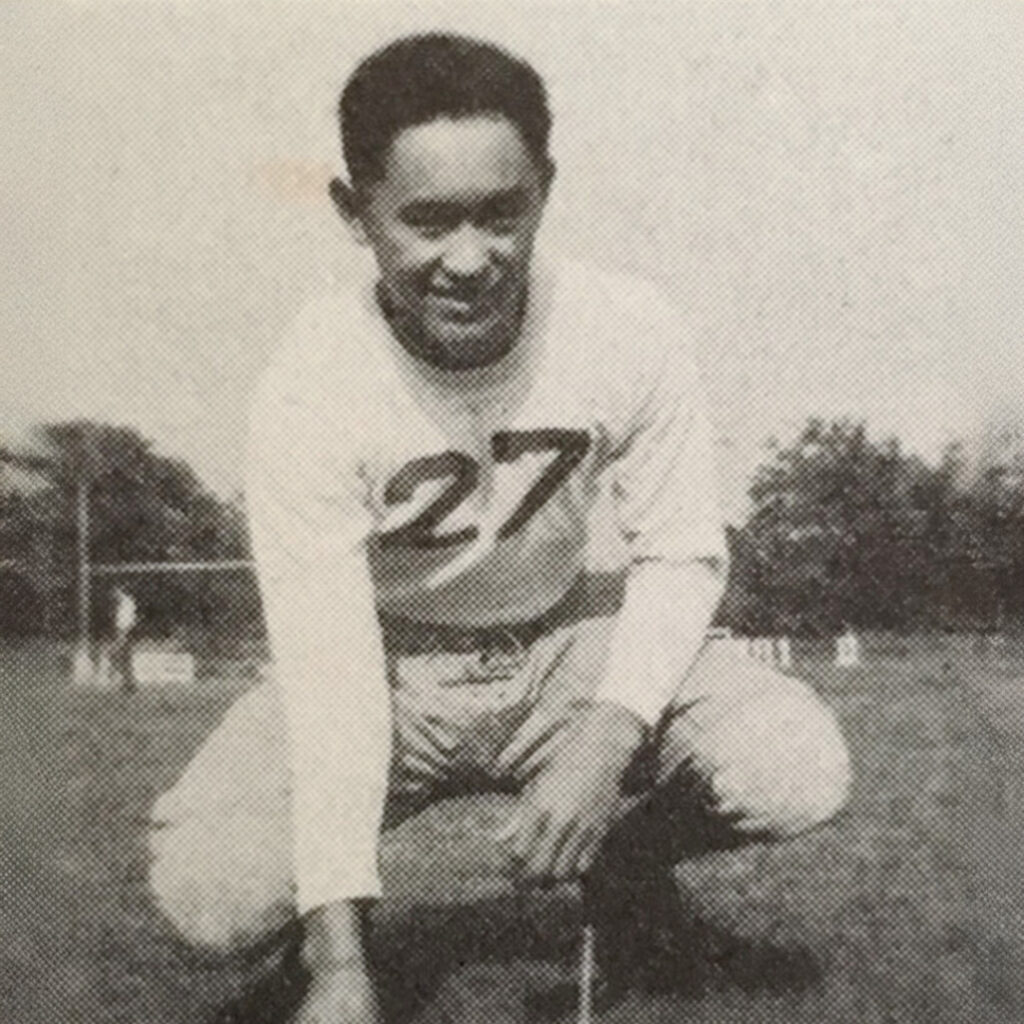

Claude entered Arcadia Elementary School in 1927, then Monrovia High School in 1935. He began Pasadena Junior College in 1939 and made it through nearly a year of classes before everything collapsed in early 1942.

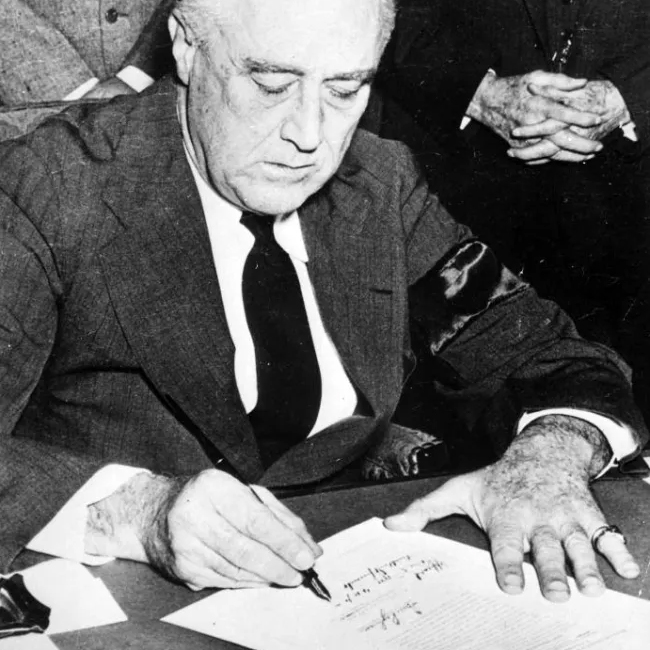

After Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 was signed. Curfew orders followed. Exclusion zones appeared. Everything familiar became off-limits. Anti-Japanese sentiment exploded. They were called names, singled out, and eventually removed.

Incarceration in Horse Stalls and Wyoming Desert

In May 1942, Claude and his family were sent to the Santa Anita Assembly Center — a racetrack turned detention site — and then to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, where they lived behind barbed wire until February 1943. He was twenty-one. He should have been studying for midterms. Instead, he was sleeping in a barrack, numbered, searched, and surrounded by guards.

In January 1943, his mother, Fuji, died suddenly from a cerebral hemorrhage. It may have been the defining loss of his early life, though like many Nisei men of his generation, he rarely spoke about his feelings.

Two months later, while still incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Claude volunteered for the U.S. Army. He left his father and siblings behind the fence and was assigned to the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), likely because his Japanese skills were stronger than most. Training took him through Colorado and Utah.

Military Career That Couldn’t Be Discussed

Claude graduated from the MIS Language School at Fort Snelling in December 1944, joining the thousands of Nisei linguists whose work shortened the war and saved lives on both sides.

After serving in the Pacific, he deployed to Japan as part of the U.S. occupation. In 1946, he parachuted into Hokkaido. He found himself meeting postwar entertainers, dining with dignitaries, and even spending time with relatives of the imperial family. For the first time in his life, he didn’t stand out for being Asian. Somewhere in those years, he fell in love with Japan — and decided to stay.

But before he could settle there permanently, he would serve again. Claude returned to combat in the Korean War. By August 1950, he had earned the Bronze Star as a 1st Lieutenant in the 2nd Infantry Division. He was discharged in Tokyo in 1953, closing a military career that had taken him from incarceration in Wyoming to battlefields in Korea. But this chapter too he rarely discussed, partly because MIS veterans had been instructed not to.

New Life in Japan

Claude remained in Japan and started over from scratch.

In 1955, he founded Pan-Oceanic Trading Company in Kanda, Tokyo — a bridge between American buyers and Japan’s postwar manufacturing boom. His main client was KTM Katsumi Mokeiten, a premium model railway maker established in 1947. The company later became Mimaki Sangyo Co. Ltd., with Claude as its president.

He spent the next five decades living between two countries that had once been at war — an American-born son of Japanese immigrants who built a business, a family, and a future entirely in Japan.

Though he visited the United States several times over the years, Japan became his permanent home. Claude Akira Mimaki passed away on August 6, 2012, at age 90.

A life interrupted, rebuilt, and lived on his own terms — across borders, languages, and histories.