In 1906, they called it “saving white children.” Nowadays, we call it racism.

October 11, 1906: San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution to force Japanese children into a segregated “Oriental School.”

Just a few months after the devastating 1906 earthquake reduced much of San Francisco to rubble, the city’s leaders began rebuilding. Not just buildings, but racial lines were redrawn, too.

On October 11, 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution forcing 93 Japanese children who had been attending public schools to transfer to a segregated campus. They renamed existing segregated school called “Chinese Primary School” to “Oriental Public School,” so that they can add Japanese and Korean children to the pool of Chinese students.

The board claimed it was necessary “to save white children from being affected by association with pupils of the Mongolian race.” Chinese children were already segregated. This order was clearly aimed at the Japanese and Koreans.

Opposition to Segregation

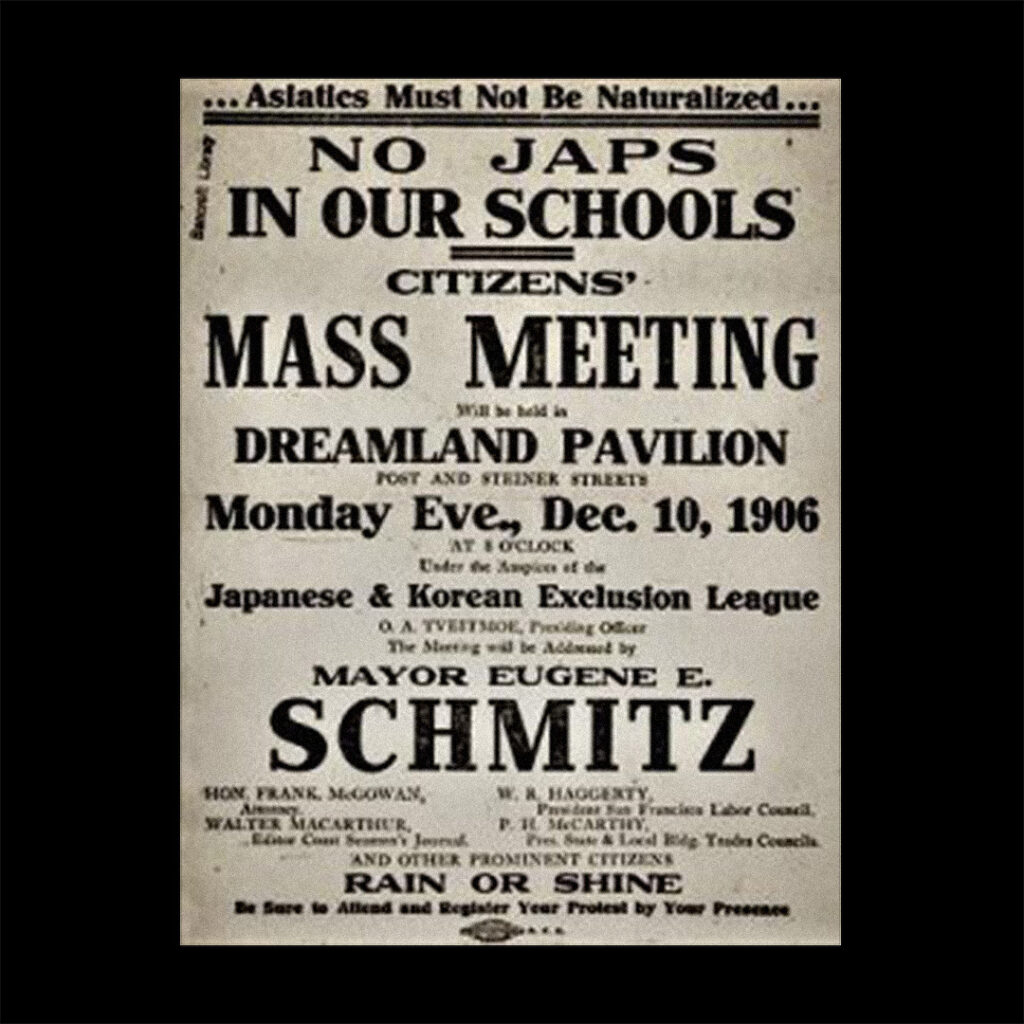

The vote didn’t happen in a vacuum. It came under pressure from the Asiatic Exclusion League, a group formed in California with one mission: to stop Japanese immigration.

This wasn’t just about classrooms. It was about exclusion of immigrants, of citizens, of children who happened to be Japanese.

Parents protested. So did Japanese American community leaders. When those efforts failed, they turned to the Japanese press and government for help.

What happened next turned a local act of racism into an international incident.

An International Embarrassment

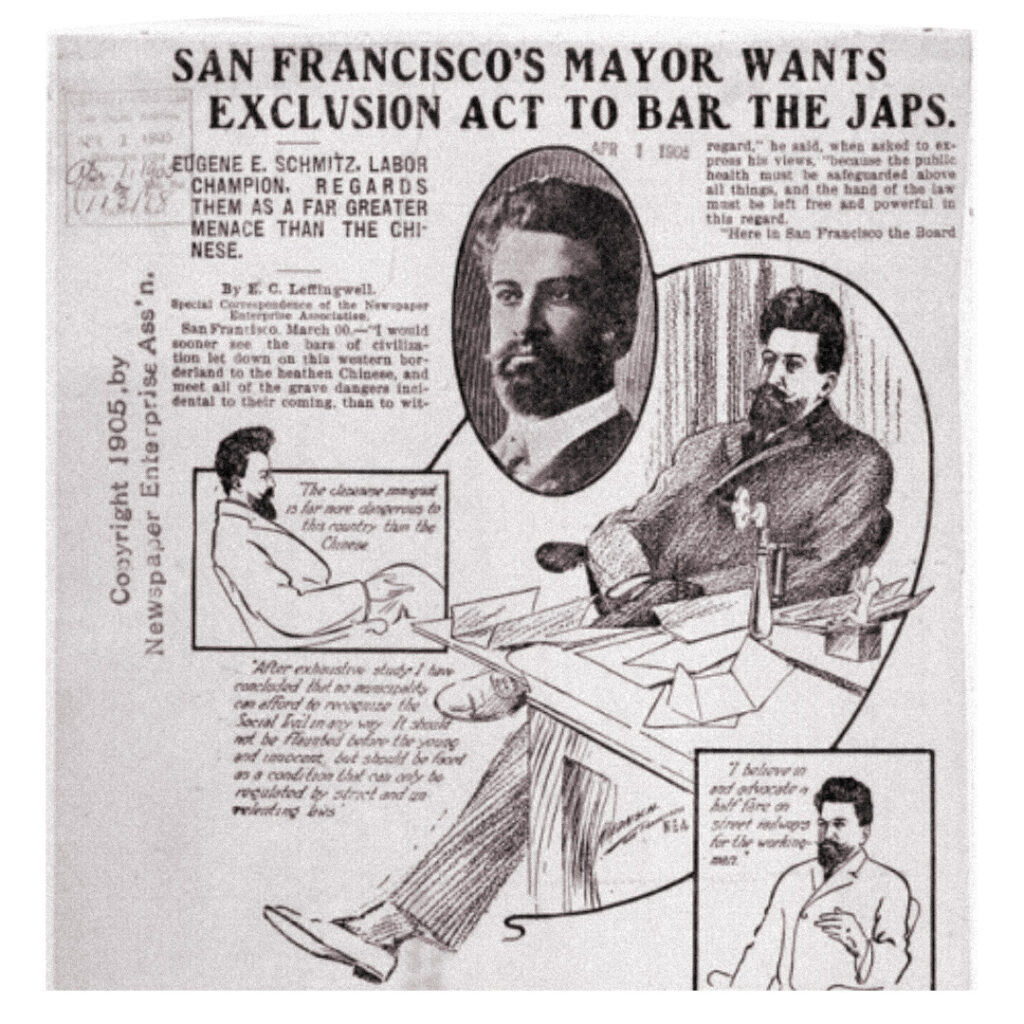

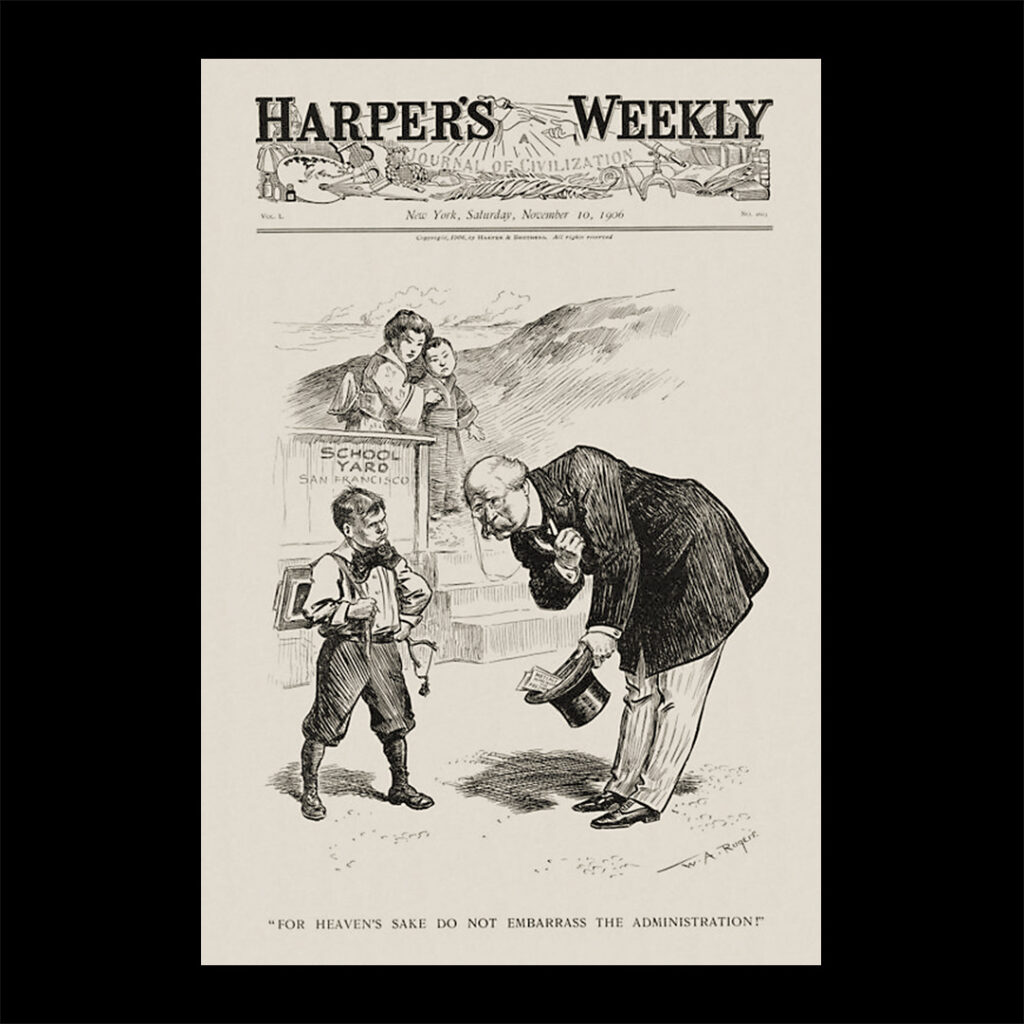

Japan, newly empowered by its victory in the Russo-Japanese War, lodged a formal protest. This posed a serious diplomatic problem for President Theodore Roosevelt, who was trying to build a strong relationship with Japan.

He sent Secretary of Commerce and Labor Victor H. Metcalf to investigate. The report was clear: aside from a few overage students, there was no educational justification for segregation.

On October 26, 1906, Roosevelt publicly denounced the school board’s decision. He later addressed the issue in his State of the Union speech, calling the move a “wicked absurdity” and warning of a growing “unworthy feeling” against Japanese people in America.

“We have as much to learn from Japan as Japan has to learn from us… No nation is fit to teach unless it is also willing to learn.”

— Theodore Roosevelt, December 3, 1906

The “Gentlemen’s Agreement”

After intense negotiations, a compromise was reached. At a January 3, 1907 meeting between Roosevelt and San Francisco representatives, the city agreed to rescind the segregation order.

In return, Roosevelt promised to curb immigration from Japan. That compromise became known as the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, an unofficial understanding that allowed the U.S. to restrict Japanese labor immigration without enacting an explicit law.

In essence, Japanese children could attend public schools again, but fewer would be allowed to arrive in the first place. For the Asiatic Exclusion League, this was better for their bigger picture — fewer Asians in America.

This wasn’t a footnote. It was a blueprint.