It didn’t last, but it left a mark.

October 6, 1942: The Jerome concentration camp opened in the swamplands of Arkansas. It would be the last of the ten War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps to open, and the first to shut down.

Open from October 6, 1942, until June 30, 1944, Jerome operated for just 634 days — the shortest duration of any of the major WRA camps, barely more than half the average length. At its peak, it held 8,497 people, but nearly 16,000 Japanese Americans passed through its gates during its operation.

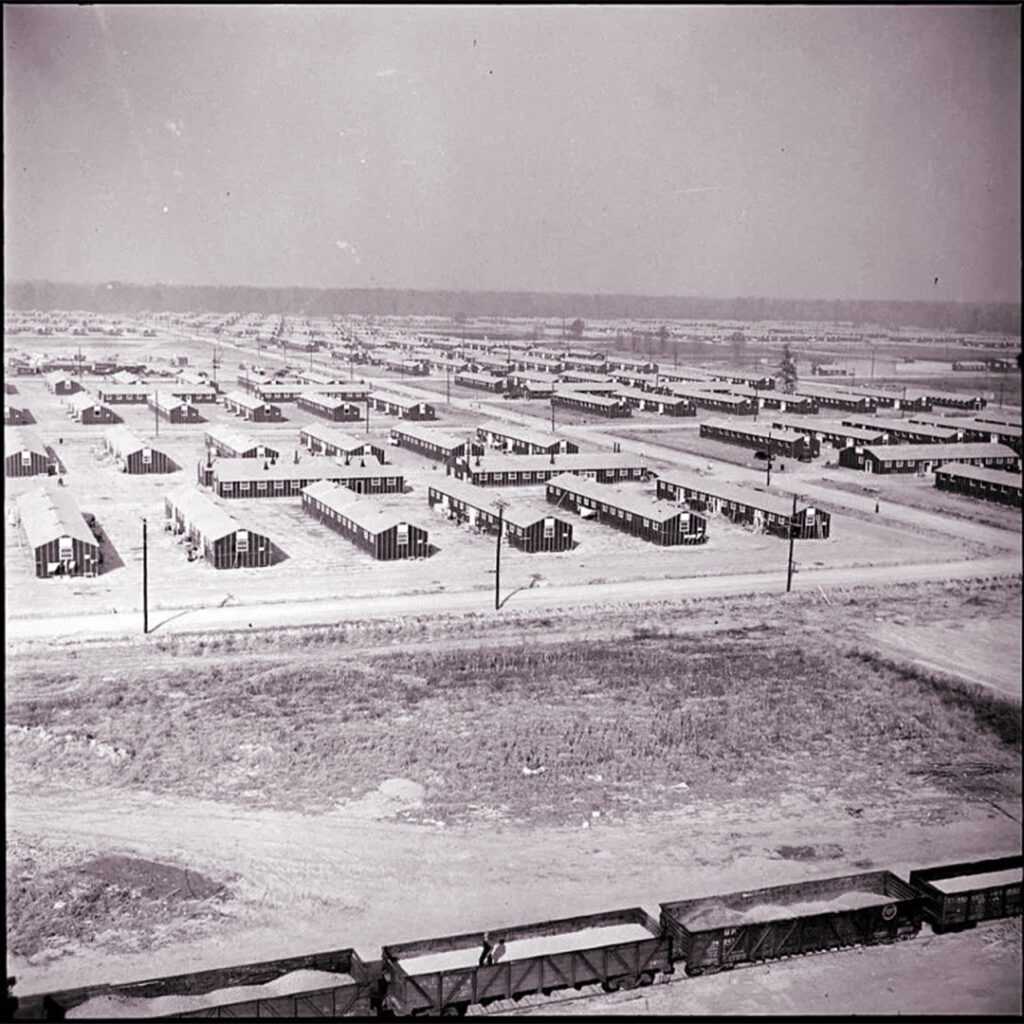

The location was harsh and remote. Humid, mosquito-ridden, and hard to access, Jerome was surrounded by dense pine and cypress forests, tucked in the Arkansas Delta near Dermott. The camp’s 505 buildings sprawled across 500 acres of what was once swamp land. Fourteen percent of its residents were over sixty years old. Nearly a third were school-age children. Thirty-nine percent were under nineteen, and sixty-six percent were American-born Nisei.

A Training Ground for Loyalty and Resistance

In early 1943, the U.S. government administered a controversial “loyalty questionnaire” to incarcerees across all ten camps. In Jerome, as in others, the questions stirred fear and resentment. Many refused to answer or marked “No” to Questions 27 and 28 — especially after seeing how the administration handled violence and distrust in the camp.

Those who responded “No” to both loyalty questions — the so-called “No-No Boys” — were sooner or later transferred to Tule Lake, which was converted into a segregation center for dissenters.

Tensions flared. On March 6, 1943, two men seen as administration collaborators were beaten by fellow inmates. Just a few months later, in October 1943, a Japanese American man named Monji Hanaoka died in an on-the-job accident. These events further fueled distrust toward WRA staff and operations.

Meanwhile, Jerome and nearby Rohwer were geographically close to Camp Shelby, where the all-Nisei 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team trained. Military recruiters used this proximity to pressure young men to enlist. On March 4, 1943, Colonel Scobey of the War Department visited Jerome and warned: If Nisei didn’t volunteer, America would see it as proof they weren’t loyal.

In total, 515 men from Jerome would ultimately serve in the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd RCT, or the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) — even as their families remained behind barbed wire.

When Jerome closed in 1944, most of its remaining population was transferred to other WRA camps. The majority — nearly 2,500 — were sent to the nearby Rohwer camp. Others were relocated to Gila River in Arizona, Heart Mountain in Wyoming, or Amache in Colorado.

Remembering Jerome

Jerome was the shortest-lived of the camps — but the wounds and stories that emerged from it ran deep. Today, little of the site remains. But its history stands as a powerful reminder of how quickly freedom can be taken, and how resilience can still flourish in even the most unjust circumstances.

In 2006, President George W. Bush signed legislation allocating $38 million in federal funds to preserve Jerome and nine other incarceration sites.

Let us not forget.

Notable Internees of Jerome:

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga – later uncovered government misconduct during the redress movement.

Yuri Kochiyama – went on to become a prominent civil rights activist.

Otokichi Ozaki – Japanese language teacher wrongfully imprisoned.

Mary Tsukamoto – educator and advocate for teaching the incarceration story.

Kazuo Masuda’s family – including his parents and sisters.