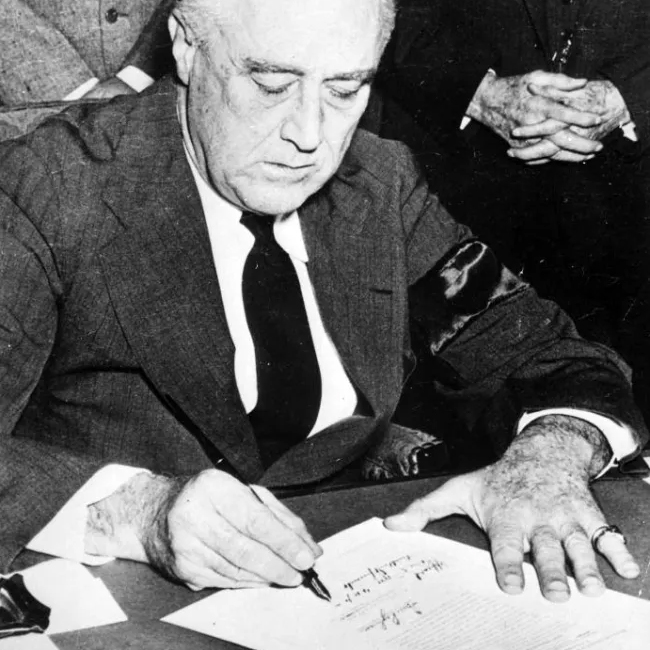

Executive Order 9066 didn’t just remove 120,000 civilians, it removed America’s human secret weapons.

June 1, 1942: The U.S. Military Intelligence Service Language School was moved from San Francisco to Camp Savage, Minnesota.

On June 1, 1942, the U.S. Army officially relocated its Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS) from the Presidio in San Francisco to Camp Savage, Minnesota.

This move was necessitated by Executive Order 9066, which mandated the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Ironically, this order displaced not only over 120,000 civilians but also the very individuals who would become instrumental in the U.S. war effort against Japan.

The new location, Camp Savage, was chosen by Colonel Kai E. Rasmussen, a Danish-born American and Japanese language student. He believed Savage was “a community that would accept Japanese Americans for their true worth – American soldiers fighting with their brains for their native America.”

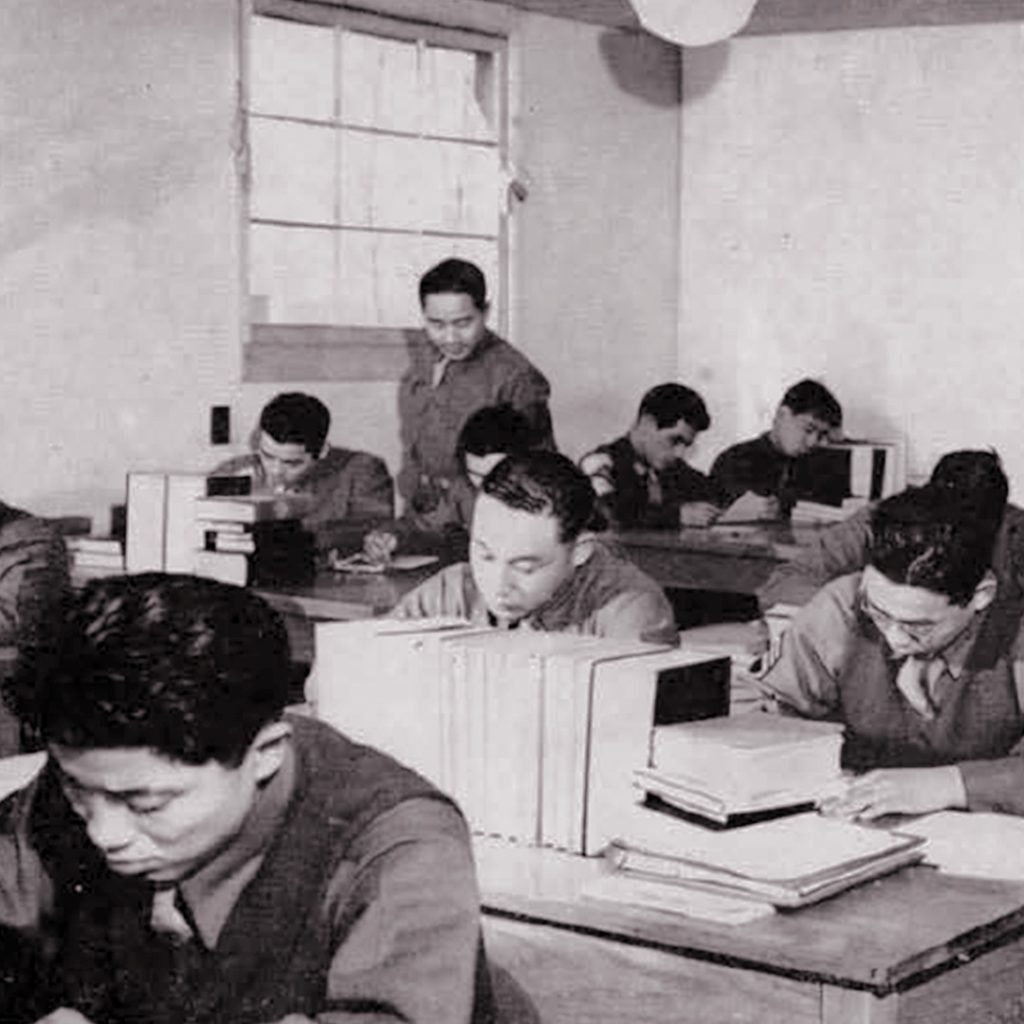

Conditions at Camp Savage were difficult in the early months of the war. The first students studied without desks, chairs, or even beds. Despite the hardship, each new class was larger than the last. For the final class, 100 instructors graduated 1,100 students.

The MISLS was primarily composed of Nisei — second-generation Japanese Americans — who possessed native-level fluency in Japanese. These individuals were trained to perform critical tasks such as translating intercepted communications, interrogating prisoners of war, and interpreting captured documents. Their linguistic skills and cultural knowledge provided the U.S. military with invaluable intelligence that significantly contributed to the Allied victory in the Pacific.

Recognizing their exceptional contributions, President Harry S. Truman referred to these Nisei linguists as “our human secret weapon” against the Japanese in the Pacific. Military leaders, including Major General Charles Willoughby, acknowledged that the efforts of the MIS shortened the Pacific War by up to two years and potentially saved a million American lives.

By August 1944, the MIS program had outgrown its facilities and was relocated to nearby Fort Snelling.

The 1940 census shows that 51 people of Japanese heritage lived in Minnesota, most of them railroad workers. By 1950, that number had grown more than 20-fold to 1,049 — many drawn by the community formed around the MIS program.

Despite facing discrimination and the injustice of internment, these Japanese American soldiers demonstrated unwavering loyalty and patriotism. Their service not only played a pivotal role in the outcome of World War II but also laid the groundwork for the eventual redress and recognition of Japanese American contributions to the nation.

The legacy of the MIS serves as a powerful reminder of how courage and dedication can prevail over prejudice, and how those once marginalized can become key contributors to national security and unity.