The earthquake destroyed half of San Francisco. The politicians destroyed the entire Japanese American neighborhood.

April 18, 1906: The Great San Francisco Earthquake changed the course of many lives, including Japanese Americans.

It was one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history. Thousands of buildings collapsed. Fires raged for days. Over 3,000 people were killed and more than 200,000 were left homeless.

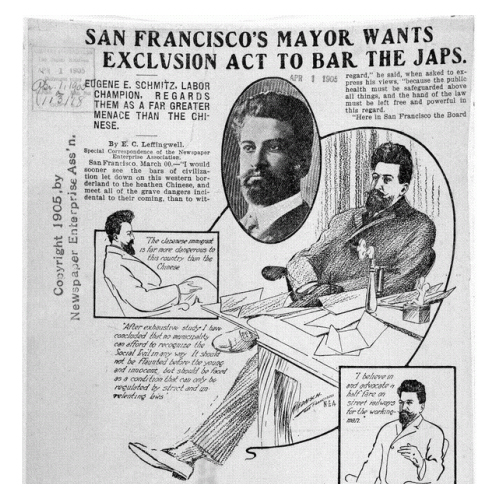

But for some city officials, the disaster also presented an opportunity to reshape San Francisco. And to do it without Asians in the way.

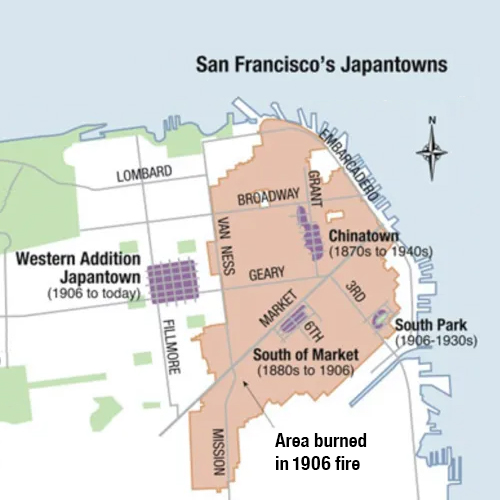

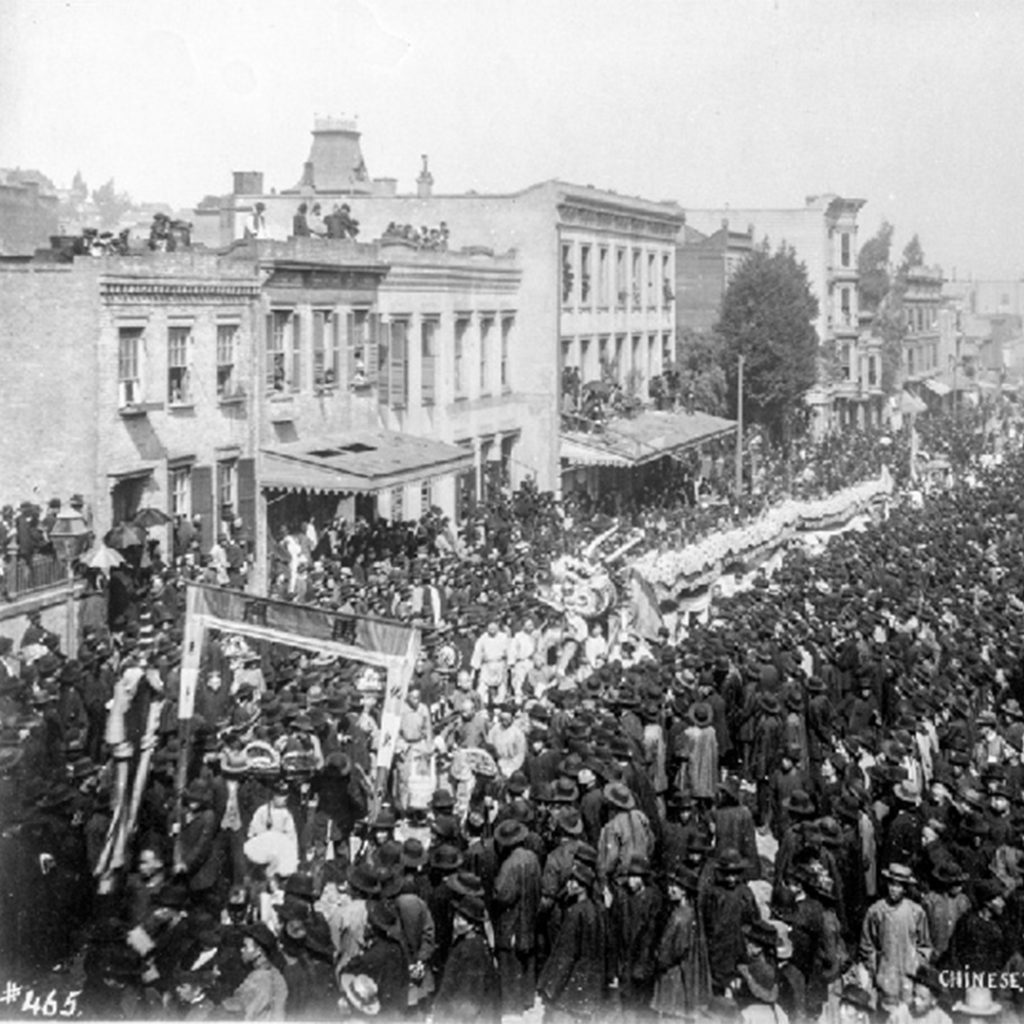

At the time, Japanese immigrants lived mostly at the edge of Chinatown. Their community was still growing — many were laborers, merchants, and students who had settled in the city in search of opportunity. Some had been in America for decades.

When the earthquake hit, both Chinatown and the Japanese neighborhood were heavily damaged. And some city leaders saw their chance.

They tried but couldn’t get rid of Chinatown. Too many of them were already there. Too many eyes were watching. Too much international pressure from the Chinese government. So they looked elsewhere.

The Japanese, they decided, could be moved.

City plans began shifting Japanese residents away from their original homes, westward — toward what would become Japantown.

The move wasn’t voluntary. Many Japanese residents, already displaced by the earthquake, found themselves unwelcome as they tried to rebuild in their original neighborhoods.

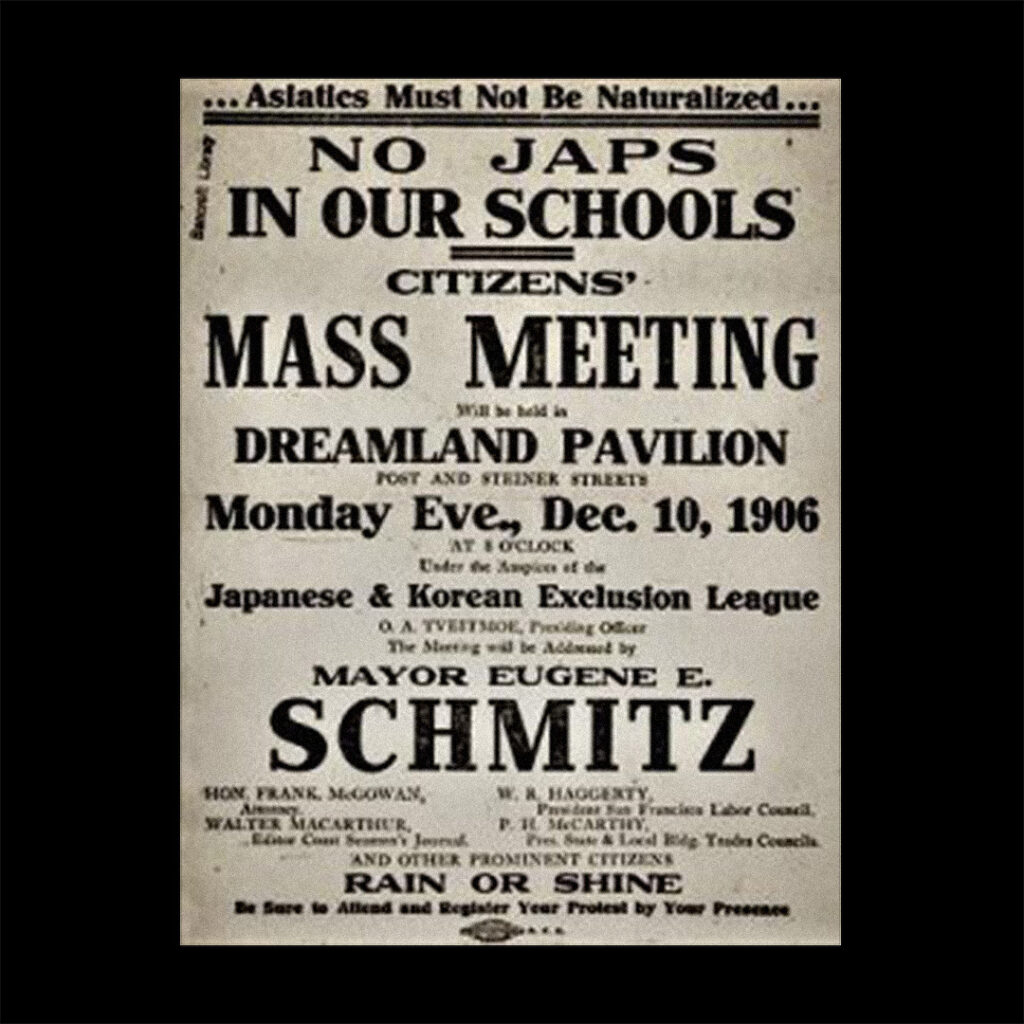

But it wasn’t just about housing. In the months after the earthquake, San Francisco’s Board of Education tried to implement a segregation policy for students of Japanese descent — grouping them together with Chinese and Korean students at the “Oriental School” in Chinatown. They claimed it was about overcrowding. But they were really talking about a different kind of “crowd.”

International backlash followed, particularly from Japan — and eventually President Theodore Roosevelt was forced to intervene. The compromise? The Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907: Japan agreed to restrict emigration of laborers to the U.S.

In return, the U.S. would avoid officially enacting segregation laws. But the message was already clear. Japanese Americans were being pushed to the edges — physically and socially.

Japantown was born not from growth, but from exclusion. It became a new center of culture and community. But its roots were laid by displacement.

Today, San Francisco’s Japantown is one of four left in California. Its history is rich. But so is the story of how it got there.