You always remember the first time. Like saying no to a racist law.

November 15, 1946: California voters rejected Proposition 15, a statewide ballot measure that would have strengthened one of the most discriminatory laws in American history. It became the first time in state history that the public voted against an anti-Asian measure.

Long before mass incarceration, California had already been laying the groundwork.

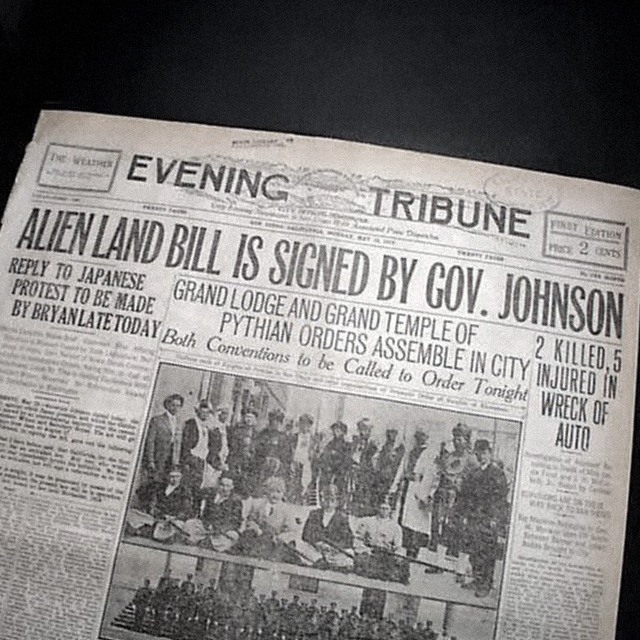

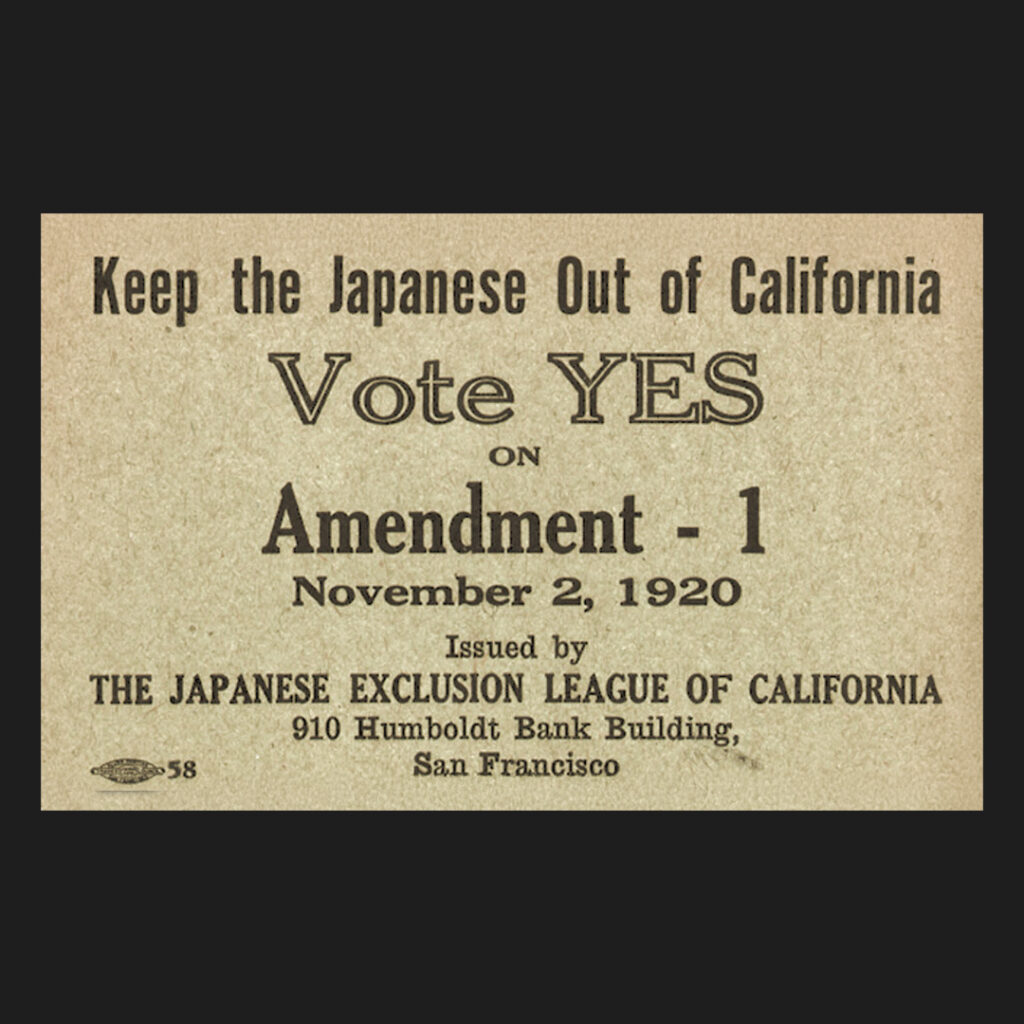

The Alien Land Law of 1913, and its harsher 1920 revision, were created to keep Japanese immigrants from owning farmland. They couldn’t naturalize because federal law restricted citizenship to “free white persons” and “persons of African descent,” and the Alien Land Law built directly on that idea. If you weren’t allowed to become a citizen, you weren’t allowed to own land.

The law was designed to crush the economic foundation of Japanese immigrant families. Or at least, it was meant to. By the 1930s, Japanese American farmers had become some of the most productive in the state, proving their resilience despite laws written to contain them. That success fed even more resentment.

The War That Changed Everything

After Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese groups like the Native Sons of the Golden West pushed for even stricter laws. When Japanese Americans were forcibly removed, many Californians believed the entire community would never return.

So when Proposition 15 appeared on the 1946 ballot, its supporters assumed it would sail through. It was framed as a “cleanup” measure to close loopholes in the Alien Land Law and prevent Japanese immigrants from ever regaining farmland.

But something had changed. The war had forced Americans to confront the contradiction of incarcerating people who looked like the enemy while sending their sons to fight for the United States in Europe and the Pacific.

They Finally Started to Win the Battles Back at Home

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team had become one of the most decorated units in American history. Stories of heroism had reached homes across the country. Public sympathy was shifting.

As Japanese American families quietly returned to California from the camps, a coalition of allies began organizing. Church groups. Labor groups. Civil rights advocates. And the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), led by Mike Masaoka, who debated opponents publicly on the radio.

When the votes came in, Proposition 15 failed: 797,067 ballots in favor, 1,143,780 against.

It was the first clear sign that Californians were willing to reconsider laws built on fear, resentment, and pseudo-science. It didn’t undo the damage of incarceration. But it cracked open a political door that had been locked for decades.

The Ripple Effects

The impact of the vote was immediate. Civil rights advocates gained confidence. Japanese American families trying to rebuild gained hope. And attorneys began preparing new legal challenges that had once seemed impossible.

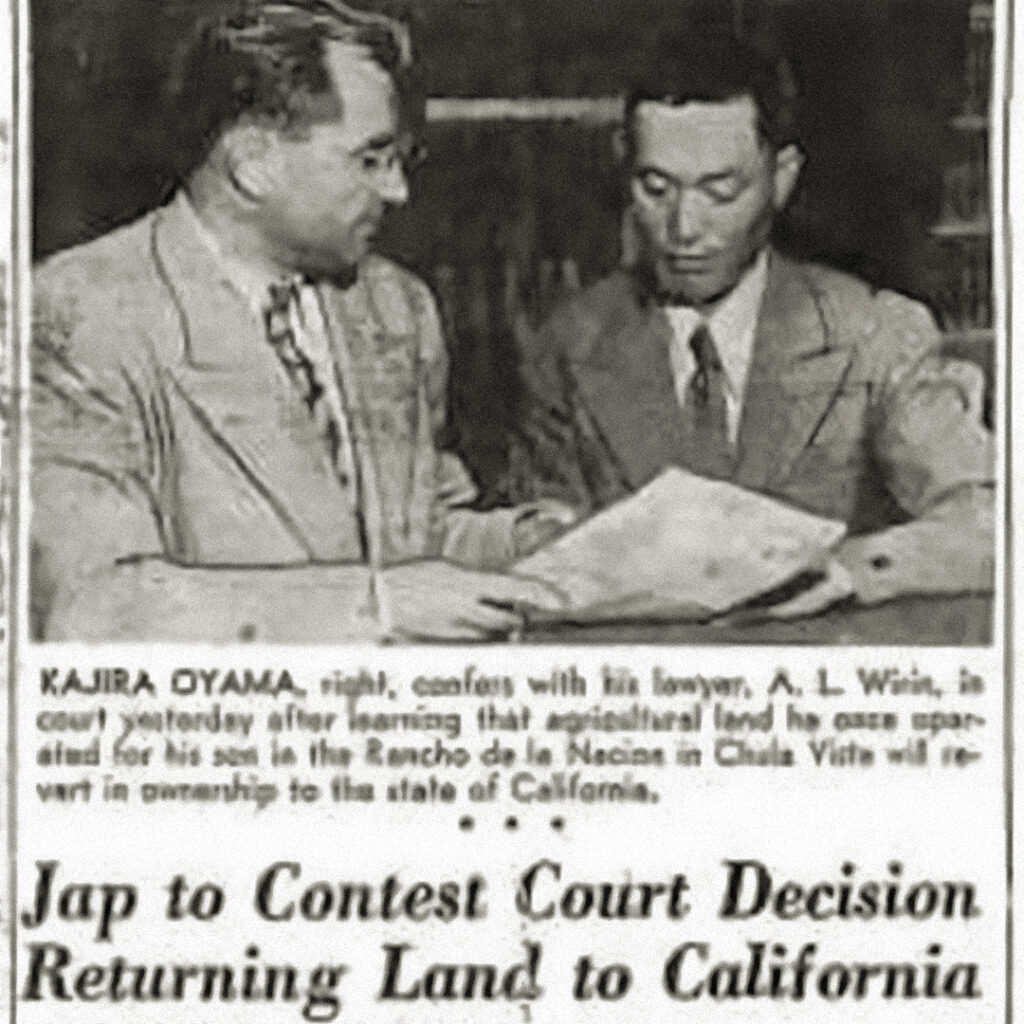

Two key cases followed: 1) Oyama v. California (1948): The Supreme Court ruled that applying the Alien Land Law against a U.S.-born citizen violated the Fourteenth Amendment, and 2) Fujii v. California (1952): The California Supreme Court struck down the Alien Land Law entirely. The 1946 defeat of Proposition 15 helped make both rulings possible.

It might be hard to believe today that this was the first time Californians rejected a racist law at the ballot box. But sometimes, one small step can change everything.