They used “Negro, Indian, and Chinaman” as evidence that Japanese couldn’t own land.

November 22, 1922: In Yamashita v. Hinkle, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Washington State’s Alien Land Law, ruling that Asian immigrants could not own land.

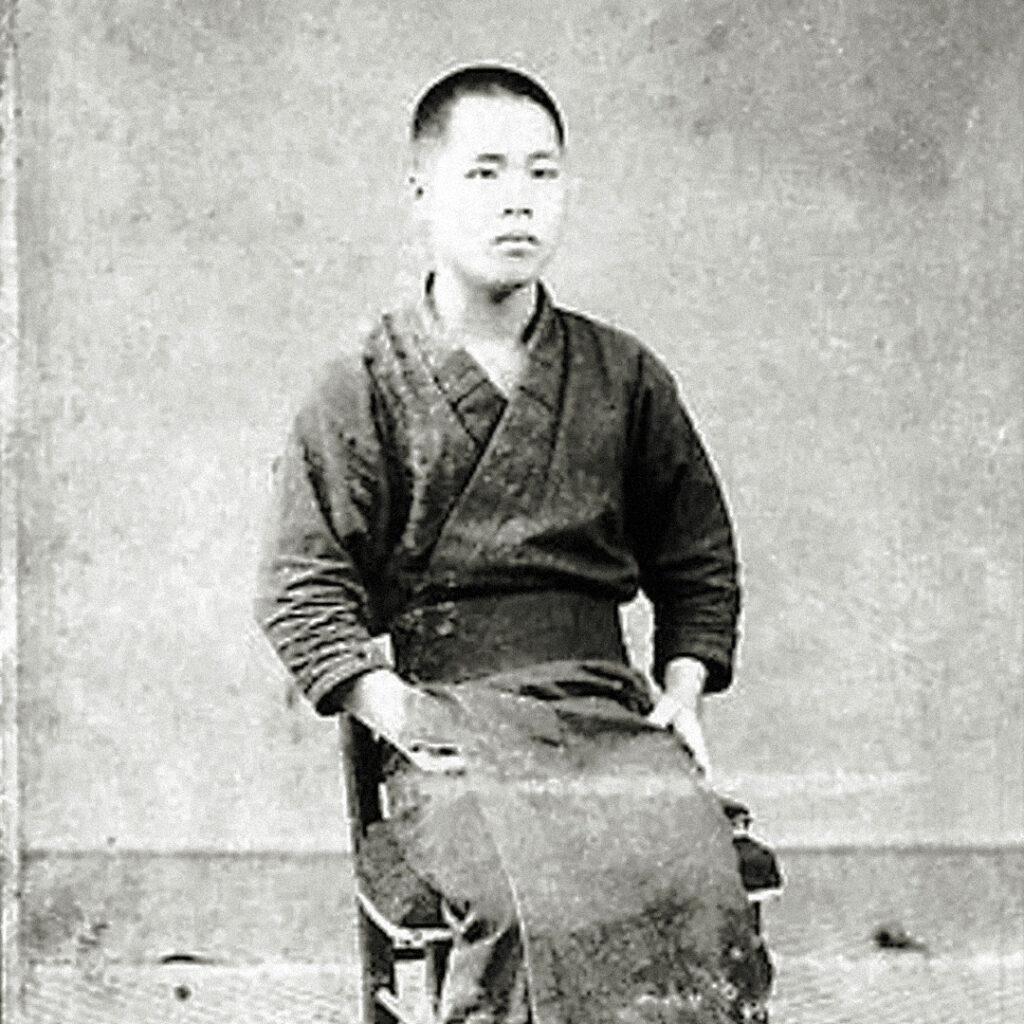

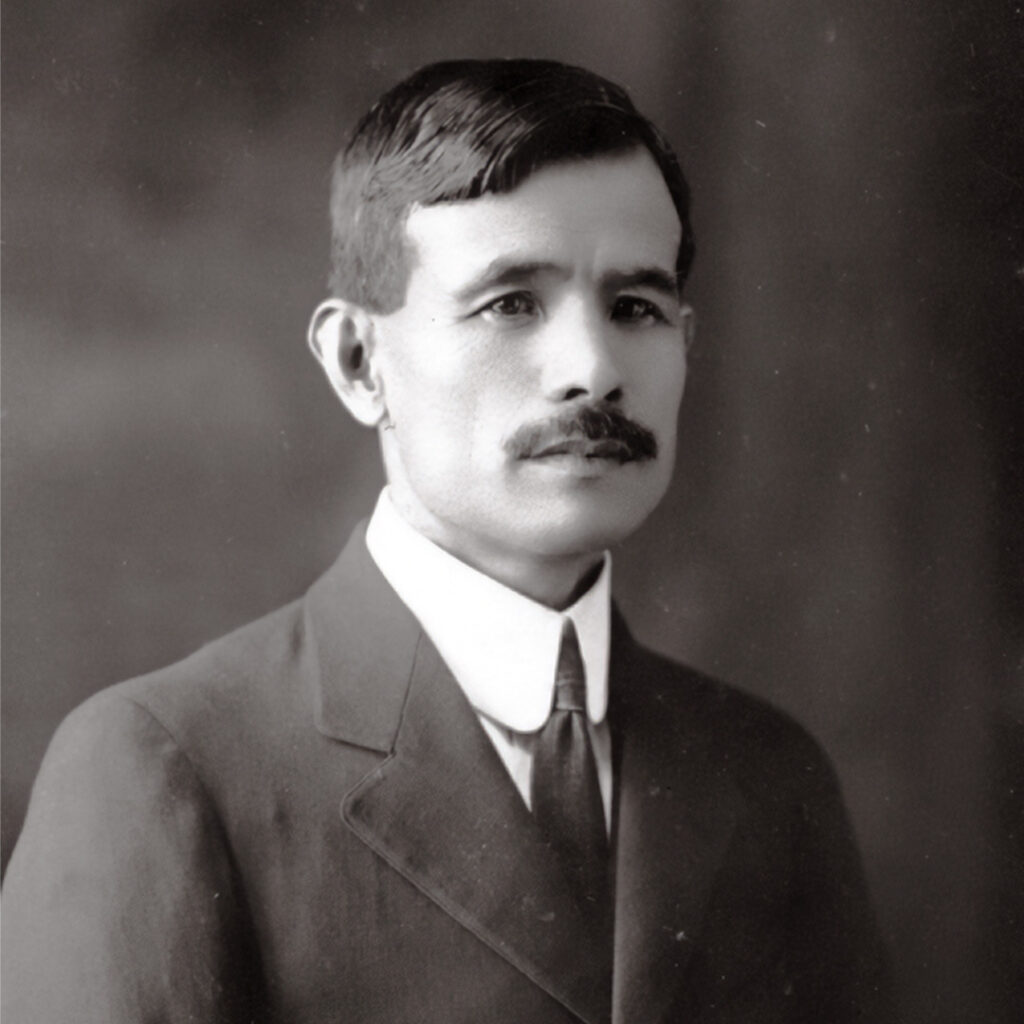

Takuji Yamashita arrived in Washington in 1893, during one of the West Coast’s most openly hostile periods toward Asian immigrants.

Anti-Japanese groups were gaining power. Newspapers warned that Japanese laborers would “overrun” the region. Lawmakers were looking for ways to keep immigrants out of public life.

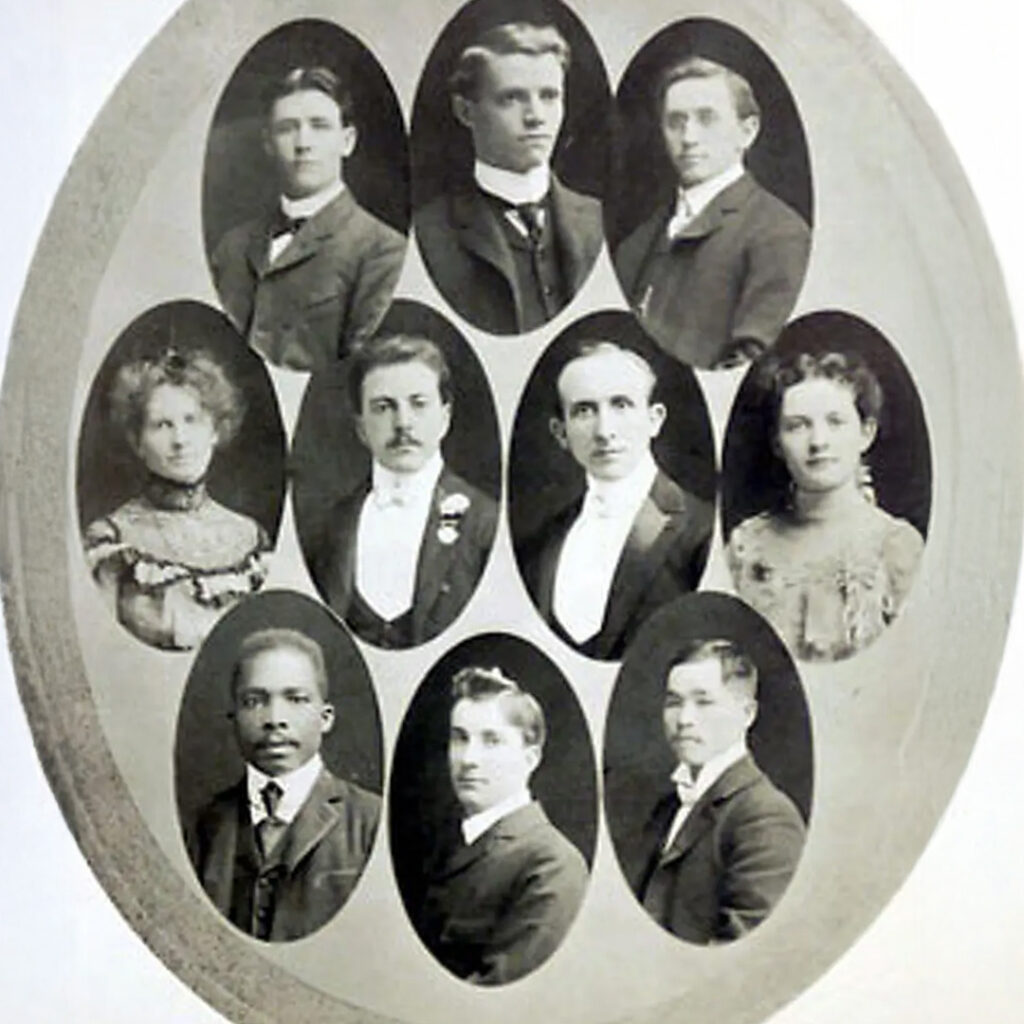

Against that backdrop, Yamashita enrolled at the University of Washington’s new law school. The program prided itself on admitting anyone who could pay the $25 annual tuition. Yamashita excelled, graduating near the top of his class. He passed the oral bar exam. He did everything the system told him to do. He was qualified to practice law in every way except one.

He wasn’t white.

Qualified, Except Not Even “Whitish”

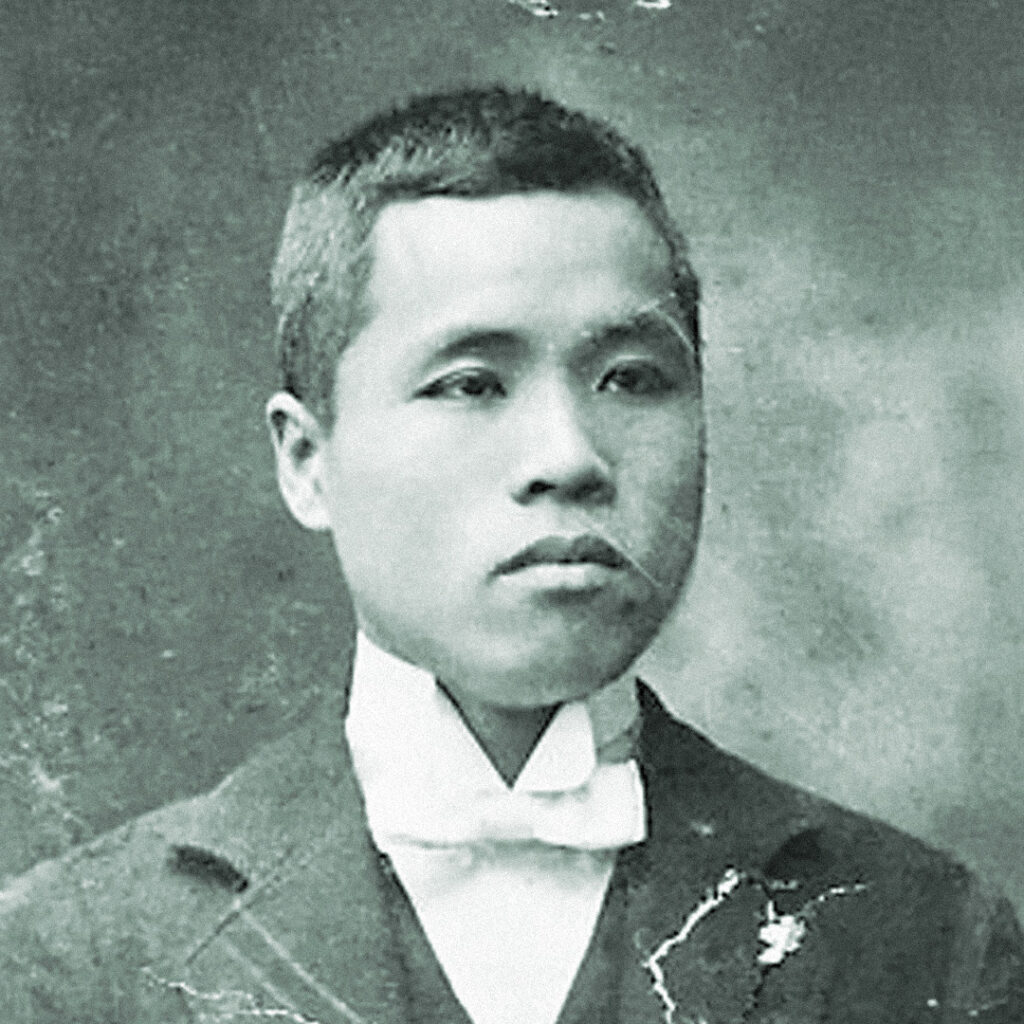

Yamashita applied for U.S. citizenship so he could be admitted to the bar. He wrote a 28-page brief defending what he believed was the core of the American promise: that the country was “founded on the fundamental principles of freedom and equality.”

Washington’s attorney general, Wickliffe Stratton, mocked him. He dismissed Yamashita’s argument as “worn-out Star Spangled Banner orations.” He insisted that “in no classification of the human race is a native of Japan treated as belonging to any branch of the white or whitish race.”

The court agreed. They praised Yamashita’s “intellectual and moral qualifications,” but still ruled that he could not practice law because he could not naturalize.

Unable to practice law, Yamashita pivoted to agriculture. He became a successful strawberry and oyster farmer, only to confront yet another wall.

How About Agriculture, Then?

Washington’s Alien Land Law, pushed aggressively by the Anti-Japanese League, blocked “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land. The law specifically targeted Japanese immigrants.

Yamashita didn’t give up. He formed the Japanese Real Estate Holding Company and attempted to legally acquire property. The state tried to stop him, accusing the corporation of being a loophole. Yamashita defended the company all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in Yamashita v. Hinkle. He lost again, because Stratton this time argued, “the Negro, the Indian and the Chinaman” had already proven that assimilation was impossible for the Japanese.

The ruling — issued the very same day as Ozawa v. United States — ensured that Japanese immigrants in Washington could neither naturalize nor own land.

Nothing Given, Everything Taken

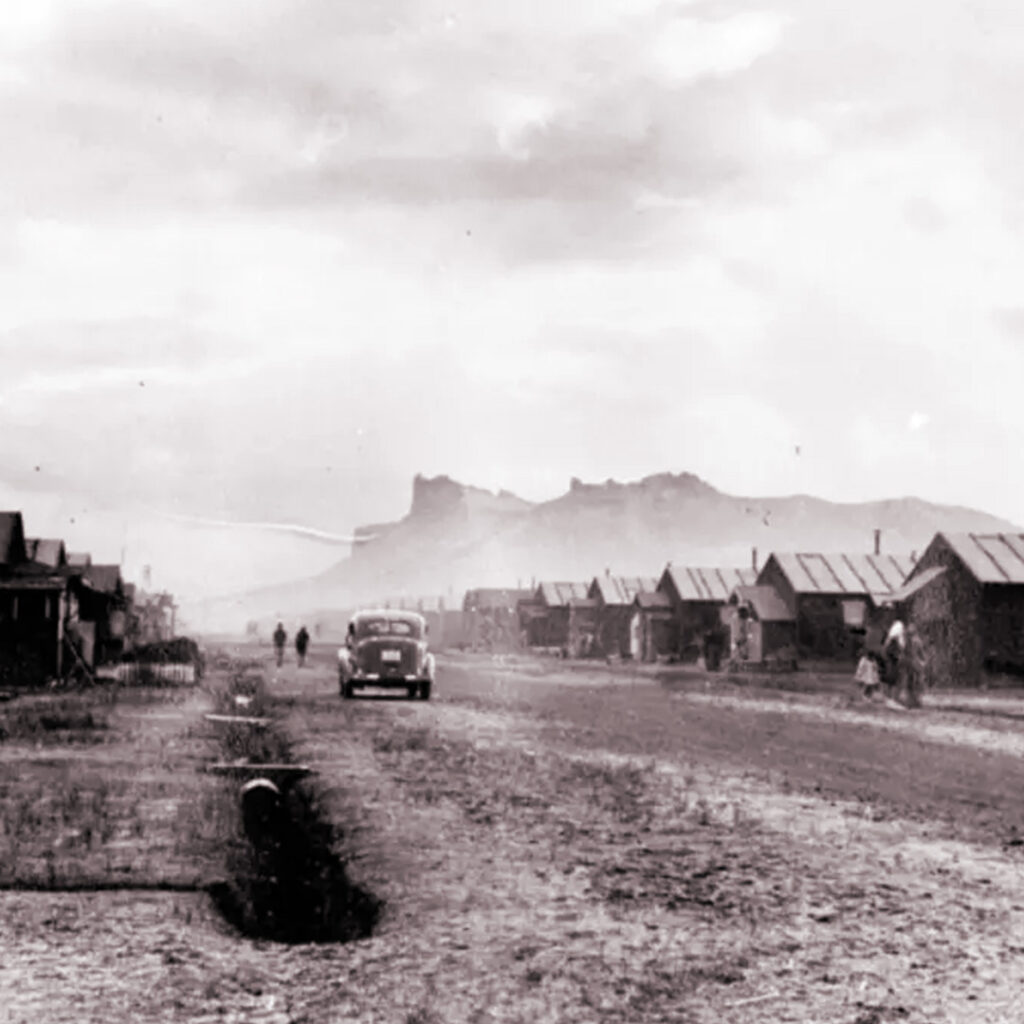

Despite the restrictions placed on him, Yamashita managed to build a successful farming operation. Then came 1942. When the government ordered the removal of Japanese Americans, Yamashita lost everything. He was forced into camp. His land, his equipment, and his accumulated success were gone.

He never regained what was taken. After the war, he worked as a housekeeper and lived quietly until his death. The man who once stood before the state’s highest court died in obscurity.

In 2001, the Washington Supreme Court finally corrected the injustice. It posthumously admitted Takuji Yamashita to the bar, acknowledging that he had been denied not because of merit but because of racism. His descendants traveled from both sides of the Pacific to witness the ceremony. The University of Washington School of Law honored him as one of the most significant figures in its history — a recognition he never received in life.