The only way Japanese immigrants could become naturalized was to become white.

November 13, 1922: In Ozawa v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled to definitively prohibit Japanese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens on the basis of race — essentially a ban that lasted another 30 years.

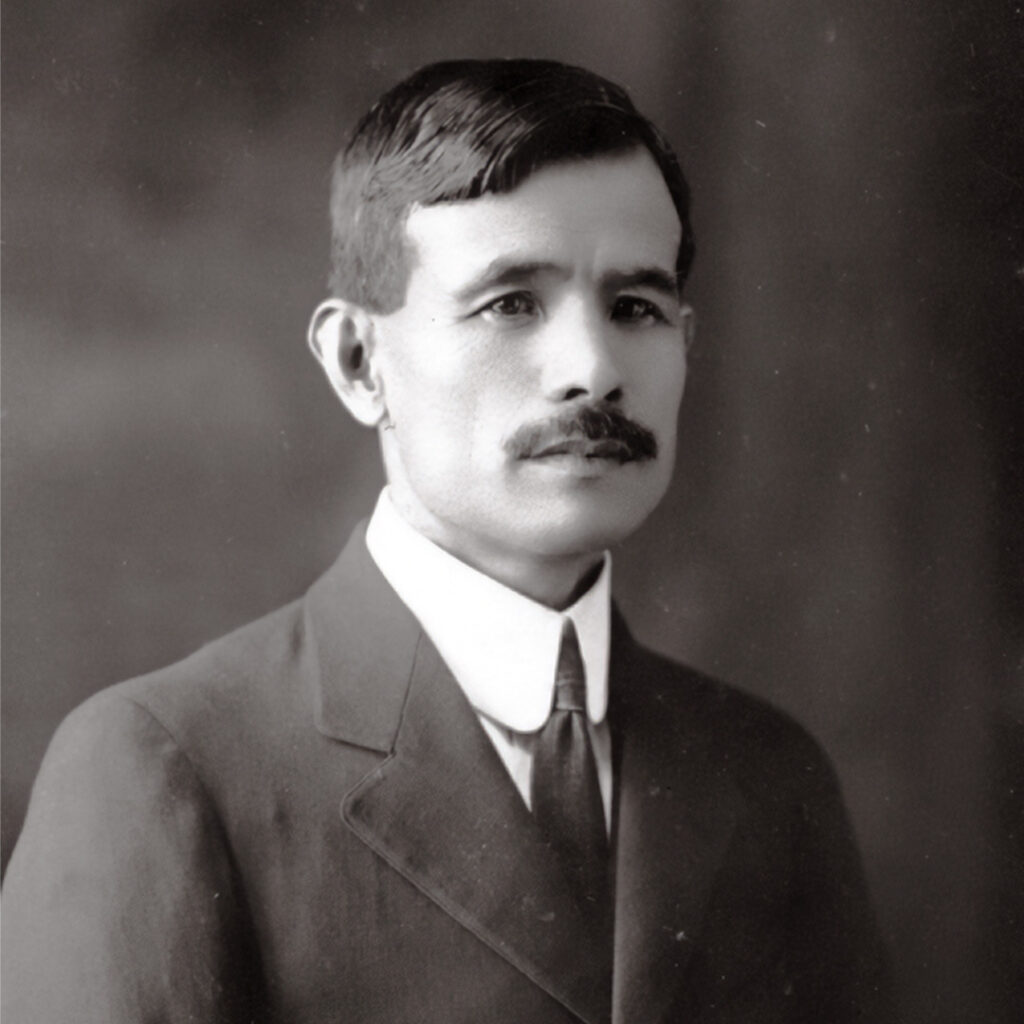

Takao Ozawa had lived in the United States for twenty years. He graduated from a California high school, attended the University of California, Berkeley, spoke English fluently, and even chose his wife because she was educated in American schools.

They raised their family in Honolulu. Ozawa never reported his name, his marriage, or his children to the Japanese Consulate, even though all Japanese subjects were required to do so. He reported only to the American government because he felt no connection to Japan — not its churches, schools, or organizations.

He sent his kids to American church and school. At home, the Ozawas spoke English because their children never even learned to speak Japanese.

He truly believed he was American at heart.

Only “Free White Persons” Allowed

He wasn’t fighting for status or privilege, only for the right to be recognized as who he already was.

On October 16, 1914, Ozawa applied for citizenship. He argued that citizenship should be based on belief and behavior, not on skin color. “In name, I am not white,” he wrote in his petition, “but in fact, I am.”

The Supreme Court saw it differently. In a unanimous decision, Justice George Sutherland wrote that “white persons” meant only people of the “Caucasian race,” and that Japanese people were “clearly of a race which is not Caucasian.”

The decision did more than deny one man’s citizenship. It cemented race as a legal boundary between “American” and “other.”

Well, Actually, What We Meant Was…

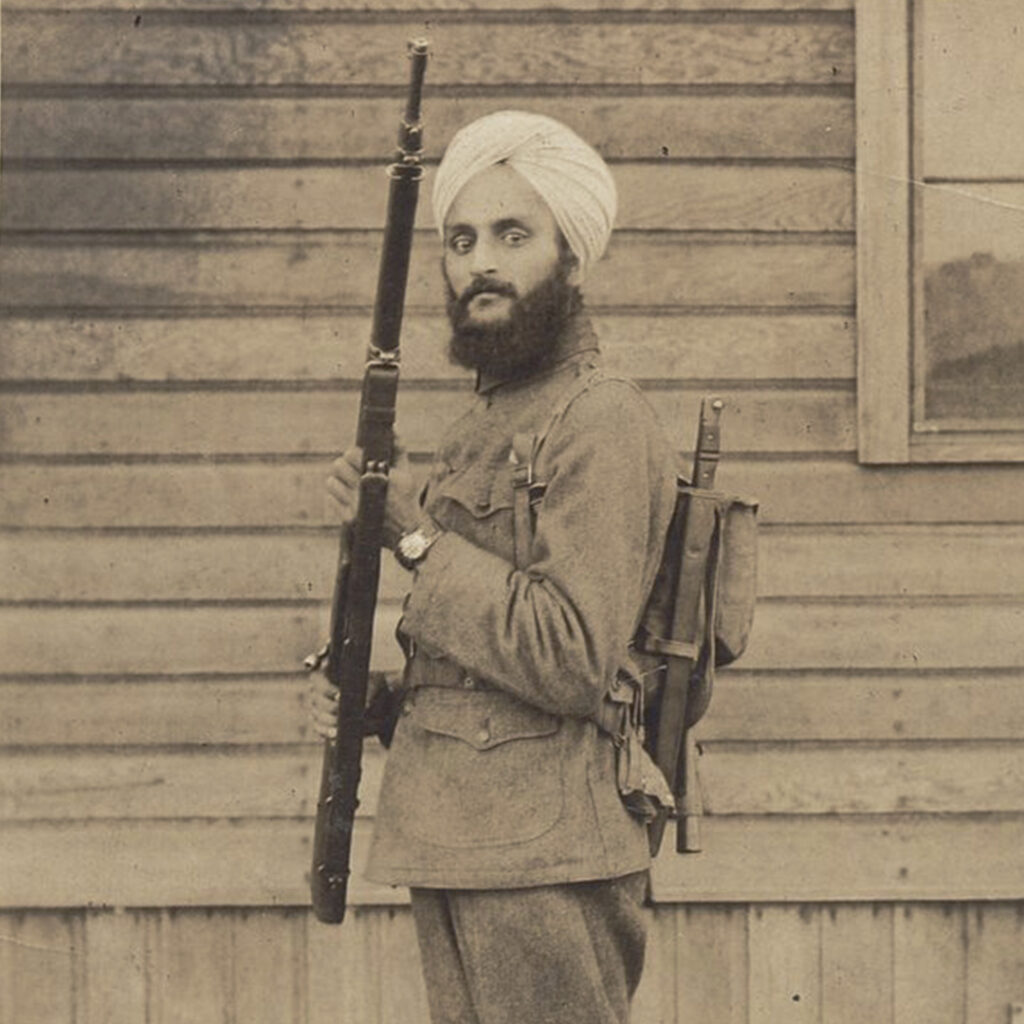

Just three months later, the Court ruled in United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind that Indians, though technically “Caucasian,” were not “white” in the way the average American would understand the term, reversing its own logic to preserve the illusion of whiteness.

Ozawa continued to appeal, but his case was passed back and forth between the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court.

By the time the Court made its final ruling, Ozawa had lived in America for twenty-eight years. The November 13, 1922 decision became definitive, and its impact lasted another three decades, through World War II’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans.

A Long Road to Justice

It wasn’t until the McCarran–Walter Act of 1952 (officially the Immigration and Nationality Act), that Japanese immigrants were finally allowed to naturalize. By then, Takao Ozawa had long passed away, never seeing the right he fought for become reality.

Yet his case remained a quiet turning point. It challenged what it meant to be “American,” something that has always been political, fragile, and unjust for many.

It was never just a question of who could become a citizen. It was a question of who was allowed to be treated as human.

And the question still continues today.